From Doom in 1993 to today, a lot has changed when it comes to shooting people in video games. Let’s slog through almost 30 years of blood and guts.

By K. Thor Jensen

If there’s a single genre that defines the video game, it might be the first-person shooter. Think about it. When a TV show wants to have a gamer character, what kind of thing is he usually playing? Nine times out of 10 they’ll be looking down iron sights and fragging foes over the Internet. There’s just something pure about the concept. No on-screen avatar to jerk around like a puppet. Your monitor is your eyes. Your mouse, your rifle. The connection is direct and immediate.

First-person shooters have enjoyed a rocky history in the nearly 50 years they’ve been around (yes, you read that right). They’ve had waves of tremendous popularity and serious decline, but they always come back as new generations of game designers bring fresh ideas and technical excellence to the concept. In this article, we trace the genre back to the beginning and try to talk about every important FPS ever released on a major platform, along with links to videos of gameplay footage. We’re going to stick with games where the player character is primarily on foot, so most purely vehicular FPS games like Descent aren’t going to be included. If we forgot anything, let us know in the comments.

See Through Your Eyes

Computer graphics was unexplored country in the 1970s. Once systems moved from punchcards to pixels on a screen, programmers started figuring out ways to make those pixels do interesting things.

Historians agree that the first real attempt at a first-person shooter came in 1973 with Maze War for the Imlac PDS-1 computers installed at the NASA Ames Research Center. Steve Colley was the first credited developer, and in the game multiple users could walk through a 3-D maze one “tile” at a time, shooting other players (represented as eyeballs) on sight. It was clunky, but nothing like it had ever been tried.

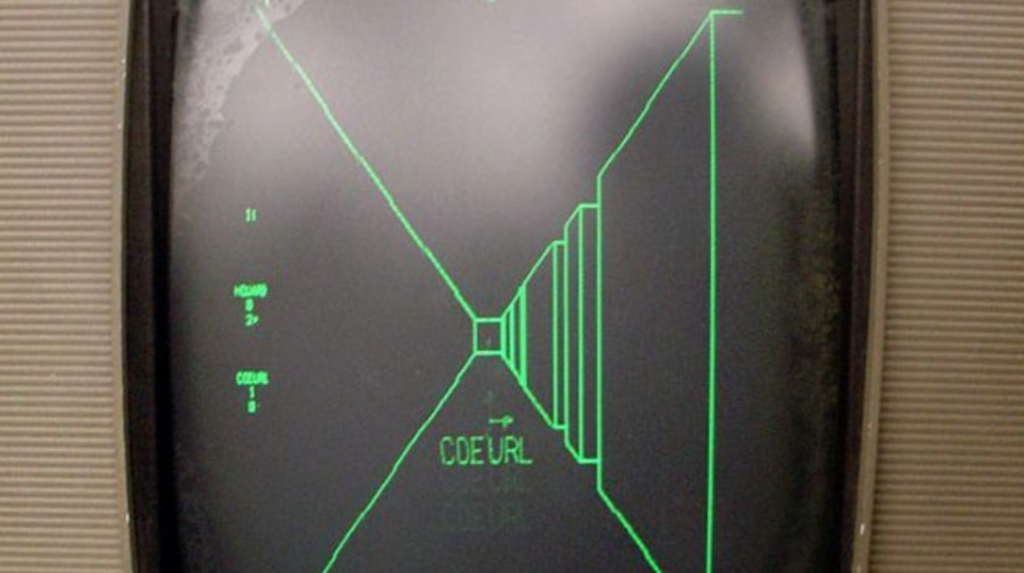

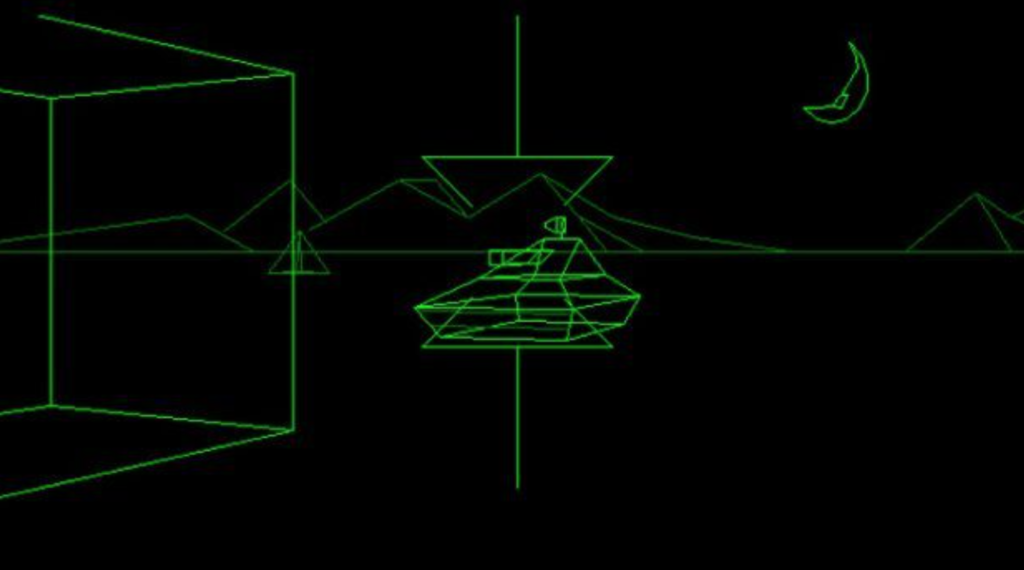

1974 saw Spasim, short for “Space Simulator,” on networked PLATO computers. This put you in control of a spaceship, not a human, but it rendered a 3D world in wireframe. Lest you think people were having fun with these early games, the hardware of the time was so primitive that the screens would refresh once a second—a truly abysmal framerate. Later iterations of the game would become Panther, a tank simulation that would make the jump to the arcades a few years later.

Insert Coin

Any history of video games has to start in the arcades. In the 1980s, this was the gamer’s primary destination, with hardware on the bleeding edge pushing new and innovative developments in game design. Although we typically associate FPS gameplay with home computers, the arcades did see a few precursors to the genre, as well as some interesting takes on the idea.

Probably the most important arcade ancestor of the FPS genre is Atari’s 1980 Battlezone. The vector-rendered game put players behind the treads of a deadly assault tank, capable of rotating and moving in any direction across a featureless landscape dotted with geometric solids and enemy foes. It’s primitive, but all the key elements are there.

One arcade game that in intensity most resembles early FPSes was Midway’s 1981 Wizard Of Wor. With players navigating a dangerous maze infested with deadly creatures – and even able to shoot each other in two-player mode – it was essentially Doom seen from above.

Released the same year as Doom, Taito’s Gun Buster was the first free-roaming sprite-based FPS to hit arcades. It controlled with the unusual combination of a joystick for movement paired with a light gun for aiming and shooting, and cabinets could be networked together for multi-player deathmatches.

Maze Runner

The first real home computer FPS was MIDI Maze, released for the Atari ST by Hybrid Arts in 1987. It put players in the role of a Pac-Man-like orb in a right-angled maze, able to move in any direction and shoot deadly bubbles at other Pacs.

What made MIDI Maze so fascinating was its networking capability. Using the MIDI in and out ports typically delegated to sound recording and processing, the game could communicate with as many as 16 players in the same maze (although anything over 4 typically caused massive amounts of lag). Competitive deathmatches were fun, especially because users could create their own mazes with a simple text editor.

In 1991, a version of MIDI Maze was released for the original Game Boy under the name Faceball 2000. Using a curious hardware hack, it enabled up to 16 of the portable consoles to be networked together for massive deathmatches. But this game was a curiosity more than anything, and didn’t sell well.

Hungry Like the Wolf

We’re almost a thousand words into this and we haven’t even hit Doom yet. Stay calm, buddy. Now’s the time when we meet the guys who would transform the world of first-person shooting forever.

iD Software was founded by John Carmack, John Romero, Tom Hall, and Adrian Carmack, all employees of publisher Softdisk. John Carmack’s technical genius enabled the team to wring incredible performance out of the PCs of the day, starting with 1990’s side-scrolling Commander Keen. When Carmack figured out a way to render 3D environments just as quickly as 2D ones, it energized the newborn company to innovate once more.

Carmack developed the concept of raycasting with an earlier title called Catacomb 3D – making the computer only draw what the player could see, rather than the whole world around him – and it unshackled 3D gaming from the world of flight simulators and other niche wonk stuff.

1992 saw the shareware release of iD’s Wolfenstein 3D, the unofficial sequel to the classic adventure game Castle Wolfenstein. While that game put players in a 2D elevated view, this new title embedded them right in the skull of Allied spy William “B.J.” Blazkowicz, massacring Krauts inside a Nazi prison. John Romero and Tom Hall pushed the experience to be fast and visceral, keeping players constantly on their toes unlike the slower-paced fare of the time.

The game saw 200,000 copies sold in a year, with publisher Apogee commissioning sequels and even releasing a collection of 800 (!) player-made levels for the game. It was a tremendous hit and single-handedly created a new genre.

And then, 18 months later, there was Doom.

Big F***ing Game

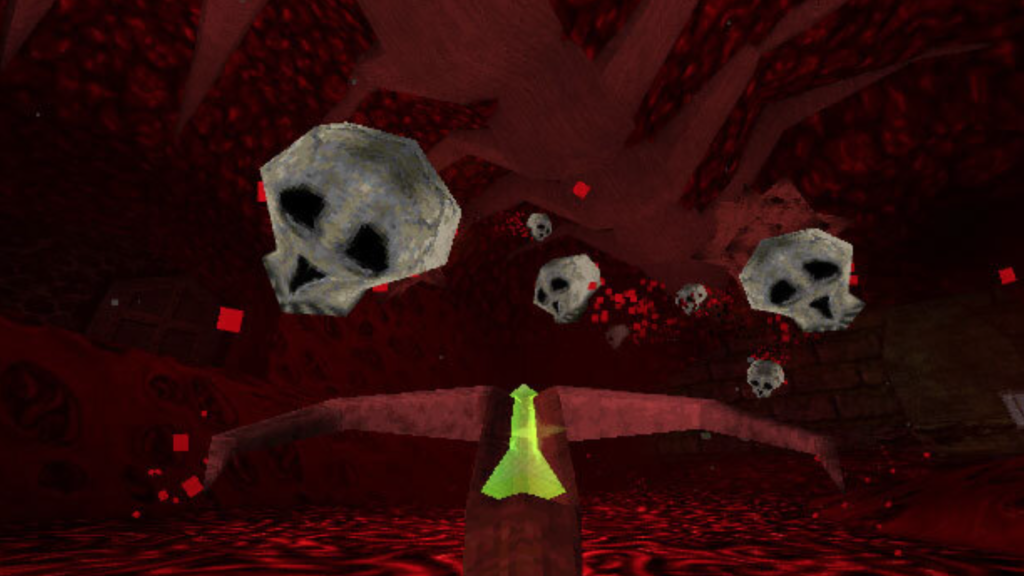

The success of Wolfenstein freed iD to follow their bliss, and they wanted more. Their next game would be bigger, faster, bloodier, and scarier, powered by Carmack’s incredibly ambitious engine. With a couple of side stops to make Hovertank 3-D (faster rendering) and Catacomb 3-D (mapping textures to surfaces), they had all the tools they needed. The team could now map bitmap textures onto 3D objects, have floors at varying altitudes, and light different areas at different levels of illumination. When attempts to gain the Aliens license fell through, Carmack revised the concept to be about technology versus demons, and Doom was born.

Protagonist “The Doomguy” is a space marine dropped into seemingly endless combat with a horde of infernal enemies, each with their own unique attacks and behaviors. One of the things that made Doom so fascinating was that its creatures lived in a simulated ecosystem and interacted with each other as well as the player. Throw in a slamming soundtrack and you had a visceral, violent experience that defined a genre.

The game was a massive instant success and inspired a host of imitators, many made using Doom‘s own engine.

Children Of Doom

Apogee’s Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold had the misfortune of being released one week before Doom, and it was already outdated by the time it hit shelves. It still saw a sequel, Blake Stone: Planet Strike. Both were competent but unexciting takes on a formula that was already growing stale.

The first big wave of shooters followed Doom‘s release, with iD helpfully licensing their engine to other companies. They weren’t worried about being beaten at their own game – a sequel was already underway, and it didn’t do anything to mess with success. Doom 2 made levels bigger and added new monster types, as well as streamlining the game’s multiplayer functionality over dial-up modems. 1996’s Final Doom was… not the final Doom, but showed off levels made by hobbyist group TeamTNT, which would shortly be acquired by iD.

Raven Software’s Heretic modified the Doom engine to let the player look up and down, as well as adding inventory management but didn’t stand out from its progenitor too much. They would release both a sequel, Shadow Of The Serpent Riders, as well as a spin-off series in Hexen. Hexen let players choose from three character classes and access side routes and hub areas that required more exploration and backtracking.

Apogee continued to spend its Wolfenstein money on more FPS games, including 1994’s Rise of the Triad, which let players choose from five different characters with different attributes. It also helped popularize the concept of “gibs,” chunks of meat blasted loose in gory fashion from dying enemies. The game also boasted destructible objects in the environment and some rudimentary physics.

Rogue’s Strife, from 1996, added some light RPG elements to the formula, allowing players to talk to NPCs in the game world and level up. It wasn’t well-received at the time, but helped influence some notable games soon to come.

The Macintosh platform had fewer developers working on it, but at least one legendary FPS landed there in the early years. Bungie’s Pathways Into Darkness, released in 1993, combined Wolfenstein-esque shooting and maze running with an inventory system and a text log of your actions.

The company’s next game, Marathon introduced the ability to wield two weapons, as well as voice chat over local area networks – a big upgrade for multiplayer gaming. This is the first FPS that I can remember playing – the newspaper in Seattle that I worked for right out of high school would have massive all-night Marathon sessions.

1994’s System Shock was an important step forward, pushing for increased immersion and a more interesting narrative. Players were trapped on a derelict space station with a malevolent artificial intelligence hindering their progress. It would inspire multiple sequels, both directly and in the Bioshock franchise, which took significant inspiration from it.

The Duke Nukem series started out as side-scrolling platformers, but with 1996’s Duke Nukem 3D it took the leap into the third dimension. This was the first FPS that really pushed its main character as a star, with the voice of Jon St. John providing wisecracks for Duke to spout as he annihilated piglike aliens.

Creators 3D Realms also launched the Shadow Warrior series, which iterated on the formula with sexual content, improved level geometry, and transparent water. Sequels and reboots followed sporadically through the years.

We could fill an entire article with the B-rate rip-offs and Doom-alikes that quickly flooded the market like Gore Galore, H.U.R.L., and William Shatner’s TekWar. None of them added anything of import to the genre – it would be up to iD to do that once more.

Pushing Polygons

The primary limitation for games built on the Doom engine was its insistence on using sprites for character and object art. They never quite meshed with the primitive polygonal worlds, but computers of the time couldn’t render both environment and inhabitants readily in 3D. Once that changed, things could get very interesting.

iD was once again the developer to lead the way with the 1996 release of Quake. Initially intended to be a 3D brawler inspired by Sega’s Virtua Fighter arcade game, the ambitious title morphed into something the team was more comfortable with – a shooter in a dark medieval world with music by Trent Reznor. Fully 3D environments gave players new movement options, and Quake embraced the concept of “rocket jumping,” using the blowback from your explosive weapons to launch your character high in the air and across the level.

There were contenders to the throne, though. In 1998, Epic released Unreal, which was built on its own engine and allowed for a number of features that were incredibly exciting. An editor that allowed for real-time geometry placement and a scripting engine made it a feast for modders, and over the next two decades, the Unreal engine would grow into one of the industry’s most reliable pieces of middleware, not just for shooters.

FPS games made using the first version of the Unreal engine include Star Trek: Next Generation: Klingon Honor Guard and the adaptation of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series.

Man On Man

Competitive multiplayer was a big part of first-person gaming from the very beginning, but the rise of the national Internet infrastructure made finding people to play with incredibly easy in the late 1990s, especially on college campuses wired with lightning-fast T1 lines.

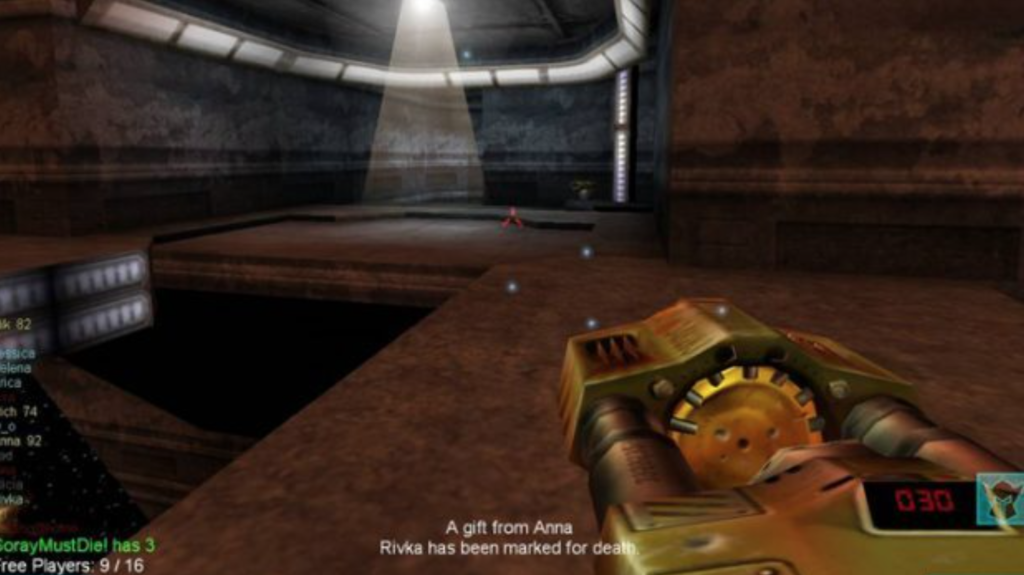

Epic dropped Unreal Tournament in 1999, one of the first purely multiplayer-focused FPS titles. The skimpy singleplayer was an excuse to train players against bots, but the meat was the online and LAN play. The game was massively successful and inspired others to work on similar projects.

iD’s take was Quake III Arena, released later the same year. Eschewing tight corridors for open arenas optimized for multiplayer, it was a beautifully tuned game with a high skill ceiling and featured an emphasis on fast movement.

In a similar vein was Dynamix’s Starsiege: Tribes, which billed itself as the “world’s fastest shooter.” The game put players in control of armed mechs in huge outdoor environments, and players discovered a movement glitch called “skiing” that enabled them to not lose momentum by timing jumps while descending a hill. Doing that let you jet across the map insanely fast.

Telling Stories

Most early first-person shooters were pretty light on the narrative. Players shot everything that moved and solved simple puzzles every so often, but characterization and plot weren’t a major concern. The release of Half-Life in 1998 forced the industry to up its game in a serious way. Valve’s breakthrough featured physicist Gordon Freeman, a silent protagonist as commonly seen in Japanese RPGs, working his way through the Black Mesa lab in a seamless world with no cutscenes. It made environmental storytelling one of the key elements of the genre.

There were some downsides to Valve’s approach, though – gone was the nonlinear, player-driven style of earlier games, transformed into a more linear experience that not many developers could pull off as well.

One of the most critically lauded attempts came with the Bioshock series, all three of which transplanted players into fascinating, carefully-built worlds where they had to wrestle with moral and ethical quandaries while blasting foes and using supernatural powers.

The Real World

As technology improved, the simulated world of first-person shooters became more and more realistic. Gamers weren’t satisfied moving around a flat plane shooting and flipping switches. They wanted to really inhabit these fantasy worlds, and to do that developers needed physics. That would open a whole new can of worms, both good and bad.

One of the first games to really push physics as a major part of the experience was Jurassic Park: Trespasser. As protagonist Anne, you could put your arm out and roughly manipulate objects like boards and boxes that responded with simulated collisions based on the laws of motion we live with every day. The problem was that their model wasn’t accurate enough, using invisible boxes around objects for collisions and making precise manipulation nightmarishly un-fun.

1998 saw the release of Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six, licensing the popular military intrigue author’s fictional universe in service of a tactical shooter that reminded players that even a single bullet could be deadly. Dispensing with the run-and-gun feel of Doom, Rainbow Six required you to plan your assault carefully, as a single mistake could be fatal. The game was a huge hit and inspired a staggering 10 sequels.

The over-the-top craziness of Quake and its children also saw a reaction from players who wanted something a little more grounded. Counter-Strike was released in 1999 as a Half-Life mod that pit teams of terrorists and counter-terrorists against each other in objective-based missions. One of the game’s biggest breaks with tradition comes in how it handles death: There’s no respawning in CS. Dead players are banished to spectate until a new round starts, meaning that every action matters. It became wildly popular and launched a competitive scene of its own.

On consoles, 1999 saw the release of the first game in the Medal of Honor series. With a story by Steven Spielberg, the game put players in the thick of World War II, with tense skirmishes featuring some of the most advanced enemy AI of the time. The game launched a franchise that would continue until 2012 on multiple platforms.

2002’s release of Battlefield 1942 would launch another long-running franchise into the space, focusing on World War II and multiplayer both competitive and co-op. The Battlefield series would encompass over a dozen games, most recently the futuristic Battlefield 2042.

Do It Your Way

In opposition to linear story-driven shooters, other designers started to push the envelope in a more expansive direction. 1998’s Thief: The Dark Project put as much focus on stealth as combat, giving players a wide range of abilities and letting them loose to complete areas in whatever way they saw fit.

This philosophy continued to 2000’s Deus Ex, Warren Spector’s landmark FPS that was all about options. Multiple solutions existed to every problem, from out-and-out carnage to hacking and sneaking, and it resulted in a genre-defining game that set a new bar for first-person adventure.

This philosophy would continue to inform game developers interested in more cerebral and immersive experiences, most notably in CD Projekt RED’s ambitious and buggy Cyberpunk 2077. These games blend traditional action with additional ways of interacting with the world, whether that be through dialogue, exploration, hacking, and more.

Console Party

First-person shooters became one of the leading reasons to game on a PC. Sure, the Super Nintendo saw a decent port of Doom, but without networking features the experience was pretty lacking. That didn’t stop some people from trying it, and a very unlikely developer managed to make a console FPS that cemented itself in the pantheon.

Early takes on the concept included 1994’s Battle Frenzy for the Genesis, Metal Head for the Sega 32X, and Super 3D Noah’s Ark for the Super Nintendo – that one a Wolfenstein reskin with a Biblical theme that managed to be the only unlicensed SNES game ever released.

Rare was a British company primarily known for their Nintendo titles, including the criminally difficult Battletoads. Over three console generations, they’d proven their value to the big N and were selected with handling a game based on the James Bond license for the Nintendo 64. That game would be Goldeneye, and it would prove that a console-exclusive FPS could play with the big boys.

Goldeneye got over the limitations of the N64 (no online play, for one) with clever technical hacks. Although the game wasn’t terribly impressive graphically, even by the standards of the day, it was smooth as butter and offered a wide selection of maps and weapons.

They followed it up with Perfect Dark, which was an improvement in many ways with better graphics, tighter enemy AI and more multiplayer options. Unfortunately, the N64 simply wasn’t able to handle everything the game wanted to do and framerates suffered – a common problem on the underpowered consoles of the day.

Publisher Acclaim, notable for their investment in licensed titles, dipped a toe in the genre with Turok for the Nintendo 64. It became one of the most successful third-party games on the system, with developer Iguana Software pushing the machine to its limits, as well as challenging Nintendo’s reputation for family-friendly games.

Other first-person shooters on early home systems included the odd Jumping Flash, a Japanese game starring a robot rabbit who could perform massive vertical hops, Kileak: The DNA Initiative, and an absolutely dismal South Park game for the PlayStation and the Nintendo 64.

Weird Stuff

The golden age of first-person shooters saw some pretty unusual takes on the genre, as everybody and their mother wanted to cash in. Forbes Corporate Warrior is, on the package, a guide to modern business. In practice, it’s one of the worst FPS games of all time, letting gamers wield “Ad Blasters” and “Marketing Missiles” to take down rival corporations.

In 1996, the General Mills corporation hired developers Digital Café to create a free game to promote their cereal Chex. The result was Chex Quest, a beloved blaster built in the Doom engine that lets you blast enemies with milk and cereal. Amazingly, the game received a pair of sequels in 1997 and 2008, and an HD remaster for the Nintendo Switch in 2022.

Terror In Christmas Town, made with the Pie in the Sky engine, is a creepy, primitive holiday-themed game that tasks you with defeating an evil polar bear who has abducted Santa Claus.

The doomed 3DO system saw the release of Cyberdillo in 1996, an ostensibly humorous shooter casting the protagonist as a roadkill armadillo enhanced with mechanical parts and set on a mission of vengeance. The game’s jokes included a “bone flute” weapon that made you go blind if you played it.

2000’s unusual Catchumen was developed by N’Lightning Software and stands as one of the most expensive Christian video games ever made, with a development cost of nearly a million dollars. The FPS put you in the shoes of a Roman student who has to venture into a series of catacombs to rescue friends and smite Satan. When you “kill” human enemies in the game, they fall to their knees in prayer.

The Waiting Game

In the early days, companies pumped out games fast and furious. The pause between Wolfenstein 3D and Doom was barely a year. But as designers got more ambitious and technology got more complex, FPS titles took longer and longer to make. The industry entered a period of long delays and release dates being postponed over and over.

John Romero tried to hop on the narrative wagon with 2000’s much-hyped, much-delayed Daikatana. Originally intended to be completed from start to finish in seven months and released for Christmas 1997, the project already looked dated and had to switch to the Quake II engine midway through development, a task that took over a year in itself. Throw in an E3 demo that ran at 12 frames per second and you got a game that wasn’t worth the wait.

3D Realms intended Prey to be at the cutting edge of technology when they started development in 1995, serving as the linchpin for the company’s own proprietary engine. Unfortunately, they couldn’t finish the job and the game was shelved in 2000, only to be brought out of hibernation and eventually released to solid sales. The 2017 franchise reboot is pretty much unrelated but great.

The king of first-person vaporware for many years was Duke Nukem Forever, which was announced in April of 1997 and finally released in 2011 – a development period of 14 years. During that time, the game shifted engines multiple times and when it came out was pretty harshly savaged by critics, putting the final nail in the franchise.

The only title that FPS gamers have been waiting longer for is Valve’s Half-Life 3, which may never happen in our lifetimes. Valve is notoriously closed-mouthed about internal development projects, and the series hasn’t seen a new game since Episode 2 in 2007.

Engine Wars

After iD came to fame with Doom and licensed its base code out to the world, other software developers saw a path to fame and fortune by creating their own 3D engines that they could reuse and license. Here’s a rundown of some of the most notable.

The “Pie in the Sky” engine was primarily the work of programmer Kevin Stokes, who used it for first-person shooters like Lethal Tender and Terminal Terror. They would then sell the tool at retail as the 3D Game Creation System, which was bought and used by a number of small teams that created games like Red Babe and the surreal hand-drawn Pencil Whipped.

Out of nowhere came a small group of developers from Croatia named “Croteam,” who boiled up their own engine to power Serious Sam, a fast-paced retro-styled run and gun title that boasted massive numbers of enemies and silky-smooth performance.

German developers CryTeam unveiled their CryEngine in 2004’s Far Cry and quickly embraced a reputation as only caring about top-of-the-line computers. They continued to evolve the engine with Crysis and its sequels, which delivered astonishing, near-cinematic realism.

Spartan Pride

After the success of Marathon, Bungie took some time off to explore other genres. But when they came back to the first-person shooter at the bequest of Microsoft, they would change the game forever. Halo: Combat Evolved was first revealed in 1999 and shipped as a launch title for the Xbox. Set in the 26th century, Master Chief battled a variety of aliens with tight controls and fun vehicles.

Halo added a number of innovations that made FPS play more doable on consoles. The most notable was probably the regenerating shield, which let players take damage and then heal up by just staying out of the action for a little bit. That made up for the decreased accuracy that playing with a controller gave. Local split-screen and LAN multiplayer were joined by Xbox Live play for the sequels.

Bungie developed two more Halo sequels before stepping away as well as a prequel and an expansion for Halo 3, and Microsoft gave the franchise to 343 Industries.

Hear the Call

The Call Of Duty franchise started with the World War II game boom of the early 2000s. Published by Activision, the first few installments in the series were competent, realistic infantry simulators that put the focus on AI squadmates. But 2007’s Call Of Duty 4: Modern Warfare marked a turning point for the franchise that would make it one of the most popular on the market.

The game took players into the world of asymmetric warfare, facing off against terrorists and insurgents across the Middle East and Eastern Europe. A potent storyline with some unexpected emotional beats, combined with innovative and responsive multiplayer, made it the year’s best-selling game.

The franchise continues to chug onwards, with recent installments moving it into the future and outfitting soldiers with superhuman movement abilities. It’s ironic that a series that started with realism has become what it has, but that doesn’t stop the games from selling.

Consoles Strike Back

Halo led the way for a first-person shooter renaissance on consoles, as developers finally figured out workable replacements for the traditional keyboard and mouse.

2000 saw the PlayStation 2 launch with an FPS, a first for consoles. TimeSplitters, created by Free Radical – a studio made up of ex-Rare employees who worked on their last-gen shooter – was a critical hit, and the sequel was even better. The introduction of a level editor gave the game a ton of replayability.

One of the biggest risks in the genre came in 2002 when Nintendo handed over the reins of their traditionally side-scrolling Metroid series to an American developer, Retro Studios. The resulting GameCube game, Metroid Prime, took the franchise in an exciting direction, emphasizing exploration and movement over shooting willy-nilly. Two sequels followed, with a long-delayed fourth installment allegedly coming to the Switch as soon as it’s ready.

Team Up

One of the most enduring multiplayer Quake mods is Team Fortress, which was originally released in 1996. The game let players pick one of nine different classes, each of which used its own weaponry and had varying movement speeds, health pools, and the like. The focus on cooperation instead of “every man for himself” deathmatch play was immediately popular, and Valve bought the team who made the mod and put them to work on both a conversion for the Half-Life engine, as well as 2007’s Team Fortress 2. That sequel polished every element of the first game and added a cartoony art style that brought it all together into one of the most consistently popular FPS titles of the last decade.

Valve also put together Left 4 Dead, which popularized asymmetric survival-based multiplayer – gamers could either control armed humans fending off the undead or powerful zombies. The game was tuned for cooperative play, with an artificial intelligence “director” that would adjust the pacing to keep things fresh. A sequel followed, and development team Turtle Rock was cut loose from Valve and acquired by Chinese megalith Tencent. Their latest game, Back 4 Blood, returns to the dish that made them famous.

Overwatch was probably the apotheosis of the team-based shooter in recent years, a candy-colored explosion of richly detailed characters with exciting abilities that intersect in all kinds of strategically interesting ways. Developer Blizzard hadn’t done much in the FPS space before this game, but they’ve shown they have what it takes to create a polished, clever take. The jury’s still out on what the sequel, dropping in October of 2022, will provide.

Other “hero shooters” with significant followings include Apex Legends and Valorant, the latter of which takes a more brutal Counter-Strike approach to gunplay.

Let’s Get Experimental

As the first-person shooter genre became codified into one of gaming’s best known, flourishes of experimentation started to crop up around the edges. Teams began to question the tropes of the genre and ask if they had to have gruff protagonists, deathmatch, or even guns.

2007’s Portal is credited for opening the floodgates. Armed with a “weapon” that opens holes in space between one location and another, protagonist Chell must escape a research facility stocked with deadly experiments by flaunting the laws of physics. The sequel added even more elements, and both games sang with smart, snarky humor.

That same year, EA released Mirror’s Edge, which was ostensibly a first-person shooter but one that prioritized movement over gunplay. Yes, protagonist Faith could wield firearms, but the meat of the game was running parkour-like through a massive world of rooftops, pipes, and shafts with incredible freedom. It was a cult hit that inspired a 2016 sequel, and the 2022 hit Neon White takes that emphasis on traversal and combines it with a clever card-based weapon system for speedruns.

One stunning recent example is Superhot, an abstract shooter that takes the frenzied pace of a typical FPS and twists it: Time only moves when you do. Stand still and bullets will hang in mid-air, but make one wrong move and they’ll plow right into your face. Each level is a tense ballet of split decisions and polygonal carnage and there’s nothing quite like it on Earth. A VR version is also available.

Other interesting FPS experiments include PS3 title The Unfinished Swan, which starts in a completely white space that the player must fill with ink to explore, the abstract Lovely Planet, and the hyper-realistic gun simulator Receiver that requires players to painstakingly perform each and every step of loading and prepping their weapons.

Looking Back

One of the most popular microgenres in the FPS space right now is being called the “boomer shooter” – games that jettison all of the fancy functionality of modern titles like Call of Duty to focus on the key gameplay elements – moving and blasting. These are often made by small development teams as labors of love, but boomer shooter influence has started to trickle into the AAA space as well.

David Szymanski’s Dusk was one of the forerunners of the genre. When it released in 2018, people didn’t know what to make of its gritty low-poly aesthetic. It goes so far as to include a fake DOS boot screen when you fire it up. But Dusk and the like don’t coast on nostalgia – boomer shooters live or die on how fun and immediate they are to play. These games have found an audience because they provide high-octane twitch excitement without any of the narrative cruft, loot grinding, or other accouterments that modern FPS games love.

Some of the other notable entries in the trend include Prodeus, which takes Doom aesthetics and runs them through a chunky pixel filter to deliver something that feels somehow older than its inspiration, as well as the gleefully silly Turbo Overkill, the only FPS that lets you wield a chainsaw on your leg.

In addition, development studio Nightdive has made a solid business for themselves remastering classic shooters like Turok, Quake, and Blood. Created when artist Stephen Kick discovered it was impossible to purchase his beloved System Shock 2 for a modern platform, they’ve brought the glory of these trailblazing old games to an appreciative new audience.

To the Future

First-person shooters show no sign of slowing down, with both legendary franchises and new installments making waves. A new Doom was released in 2020, the Wolfenstein series is hot again, Call of Duty continues to see a game come out every year or so, and the “games as service” trend keeps games like Overwatch and Destiny 2 updated with new content on a regular basis.

Virtual reality is also asserting itself as a major platform for the genre, which makes sense. There hasn’t been a truly system-selling title among them yet, but some very strong offerings like PSVR’s Farpoint and Valve’s long-awaited Half-Life: Alyx are proving the potential is there. Control issues are still the biggest drawback to VR games – it’s hard to really feel like you’re sprinting and strafing while standing still.

So, what’s the future of first-person shooting? The genre has come a long way since those early days, and technology lets us pursue unmatched realism—or go in the opposite direction and create shooting experiences that are artful and surreal. We’ll be there, no matter what they do, circle-strafing and rocket jumping for our lives.