By Ken Miyamoto

What is the difference between writing an animated screenplay and a live-action screenplay — and what should screenwriters know about pursuing a career in animation writing?

Writing feature screenplays and pursuing a career as a feature screenwriter is a pretty straightforward journey when you break it down. But writing animated screenplays and pursuing a career in animation adds additional elements to the journey. The scripts need to be slightly different, and the career approach has additional nuances that you need to be aware of.

Here we offer a simple guide to becoming informed and understanding those nuances.

HOW TO GET YOUR START IN ANIMATION

CONSIDER BECOMING AN ANIMATOR

There’s an inescapable truth that trying to sell animation screenplays on spec (writing them under speculation that you’ll sell them to someone) can be much more difficult than trying to sell a spec script intended to be a live-action feature.

Animation houses usually develop animated projects from within. And those projects are usually developed by animators. Animation is an animator’s medium. There’s no escaping that.

So, before you begin to pursue a career in writing for animation, consider trying to become an animator yourself. That’s the easiest and most direct way into animation writing.

- You can pursue a degree in animation or computer graphics.

- Disney offers college students internship programs and offers entry-level growth opportunities for recent grads and those new to the animation industry.

- And there are many other opportunities online as well.

But don’t worry, non-animators have succeeded in animation writing as well.

JUMPING FROM LIVE-ACTION TO ANIMATION

Yes, being an animator helps you ten-fold when it comes to writing animated screenplays that get produced. All of the Pixar titans (Unkrich, Lasseter, Docter, Stanton) began in animation before writing Pixar’s biggest hits. But that doesn’t mean that being an animator is the only route in.

After graduating from college, Oscar-winning screenwriter Michael Arndt first started out as a script reader for production companies. He then became the full-time assistant to Hollywood actor Matthew Broderick. In 1999, he decided that he wanted to pursue screenwriting full-time.

Arndt wrote and revised the script for Little Miss Sunshine over the course of a year. He got the script to a producer and ended up selling it for $250,000. The script was then in development for a few years until it was finally produced, leading to critical acclaim, box office success, and an Oscar for Arndt.

Pixar then hired Arndt to write the screenplay for Toy Story 3, based on Andrew Stanton’s treatment. He was nominated for an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

If writing for animation is your dream, but you don’t want to become an animator to do so, there are options. You can impress an animation house with live-action success or with strong animation and live-action scripts as samples.

WHY SHOULD YOUR SCRIPT BE ANIMATED?

Too many screenwriters have sent screenplays out to animation studios without the initial intention of creating a story bred for animation. Animation isn’t a fallback or secondary option for the marketing of your screenplay.

But maybe you should consider writing for animation.

You need to explore what animation can bring to your screenplays and stories. You need to ask yourself why your script should be animated — and why you should approach animation houses and producers. One of the first things they will ask you is: “Why should this be an animated movie?”

The best genre options for animation include:

- Fantasy

- Science Fiction

- Children Book Adaptations

- Comic Adaptations

Animation can bring these types of stories to life in a way that live-action can’t, even in this day and age of CGI. The medium allows creative and stylistic visuals and imagery to come to life — visuals and imagery that wouldn’t translate as well to live-action. And some that just wouldn’t be possible in live-action.

There has to be a reason, though. There needs to be a communicable pitch for why your story is perfect for animation. Animation can’t just be a marketing option for your screenplay.

SCREENPLAY FORMATTING: LIVE-ACTION VS. ANIMATION

The initial animation screenplay format is no different from what you would see with a live-action feature script.

You use the same core elements of screenplay format:

- Scene Heading

- Scene Description

- Character Names for Dialogue

- Dialogue

And you can expect the same with writing animated TV series episodes as well.

However, there are basic nuances that you should consider adding to your animated screenplays.

VISUALLY-ENHANCED CHARACTER DESCRIPTION

This harkens back to showing us why your script should be an animated feature. When you introduce your characters within the screenplay, seek out opportunities to add a little visual flair.

Maybe your character has:

- Big eyes

- Exaggerated big ears

- An extremely small frame

- Vibrantly colorful clothes

It’s good to have just a line or two of description that screams animation. You don’t want to overstep your bounds, though. It’s an animator’s medium. The animators are going to take your script to the animation-level with their own character designs, but you can offer a couple of broad strokes to work from.

SCENE DESCRIPTION FREE OF BOUNDS

The great thing about writing for animation is that anything is possible. You no longer have to worry about the constraints of live-action features, where you can (and should) worry about having too many exotic locations, unrealistic action sequences, etc.

Go nuts. Explore and create vibrant worlds. Put your characters through hoops and hurdles that live-action wouldn’t allow. Create worlds that scream for animation and excite animators. Give them a reason not just to want to accept the challenge of bringing such a unique and original world to life — make them feel the need to do it by creating something so unique and special.

FANTASTICAL PROPS AND VEHICLES

Don’t be afraid to be weird and strange. Fill your world with things we haven’t seen before — or different and exaggerated variations of what we have seen. The animators can create whatever you envision.

A normal live-action script would just say car. You can take that to the next level with an additional line or two of description to capture an enhanced visual.

WHAT TO KEEP IN MIND AS YOU CRAFT YOUR STORY

READ A LOT OF ANIMATION SCRIPTS

If you want to know how to write a great animated script, one of the best ways to learn is to read great animated scripts.

What are your favorite animated films? Find those scripts and read them! Do a lot of them come from the same production company? Find out what that particular company’s philosophy is on storytelling, whether it’s Pixar, Laika Studios, or Studio Ghibli. (Quick Note: Pixar is very outspoken about its approach to telling stories and Hayao Miyazaki is also incredibly generous with his insight into Studio Ghibli’s storytelling method.)

Conversely, though, don’t just read great scripts — read the less-than-great ones, too. Diagnose what these scripts lack. Is the dialogue unnatural? Are the characters flat and one-dimensional? Is the exposition too heavy-handed? Are the plot points unorganized and hard to follow? Understanding how other screenplays miss the mark can really help you avoid missing it yourself.

If you want to read some great animated screenplays, check out The Script Lab where you can download and read them for FREE! Here are a few to get you started.

DETERMINE WHO YOUR AUDIENCE IS

You’re not going to pitch an animated series or feature in the line of Family Guy or Sausage Party to Pixar or Disney. And you also need to understand how difficult an adult-oriented animation project will be to get off the ground.

The major animation houses like Pixar, Disney, and Dreamworks have a brand. They’re not going to suddenly roll with adult-oriented animation.

So, whether you want to create four-quadrant family movies, animated children series, anime-level action/horror, or adult-oriented animated series, go in knowing what your demographics are and do your best to study them and cater to those audiences.

EXPLORE THE COMMON THEMES

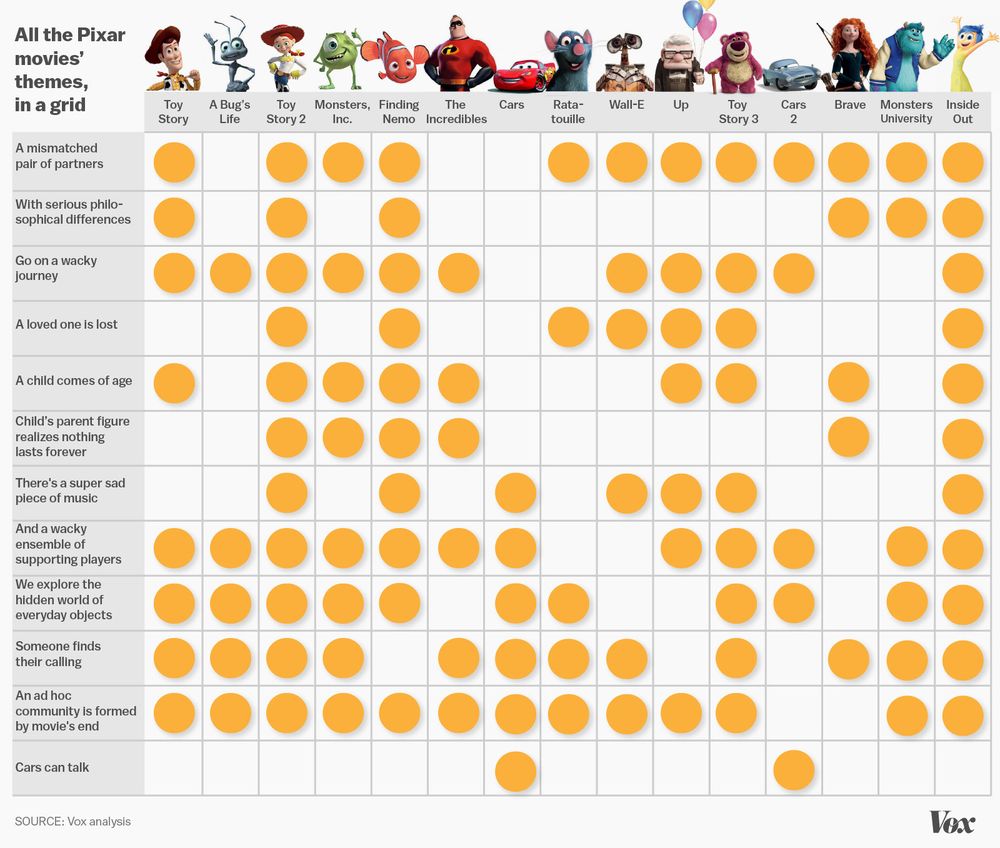

A few years back, Vox created a grid to showcase the themes found in most Pixar movies.

Themes are important in any storytelling. They can be developed early on in the writing process and used as a compass to guide the story and characters. They can be inserted during the writing process to better touch and engage an audience.

These above principle themes found in Pixar films prove that because they are so widely used throughout their catalog of films, and because Pixar has been so successful as a result, screenwriters should take note and consider exploring such themes within their own animated screenplays.

Disney and Dreamworks have embraced similar themes as well. The best thing that screenwriters can do is know and understand the animation realm. There are common successful themes that exist. And those themes are successful for a reason. Don’t be afraid to embrace them.

FEATURE A WORLD WE HAVEN’T SEEN BEFORE

We’ve seen toys coming to life, house pets wreaking havoc, and zoo animals exploring the city.

If you want to succeed in animation writing, you’re going to need to give us something new. If you want to entice animation studios to take notice of your writing, you’re going to need to go to extremes to stand apart from their own animators and the rest of the screenwriters trying to break through just like you.

The easiest way to engage them is to offer something they haven’t seen before. And you do that by exploring worlds that animation hasn’t yet.

Before Toy Story, we never experienced the concept of a world where our toys come to life when we’re not looking.

Before Shrek, we never thought about a world where all of the fairy tale characters and creatures we grew up with lived in the same realm together.

Before Inside Out, we never imagined a world where our emotions are living and breathing characters.

What’s so special about the world in your animated screenplay? Are you giving us more of the same, or are we going to be transported to a world we never thought to imagine? That is the secret sauce to any successful animated movie or series.

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, and the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed starring Duane “Dog the Bounty Hunter” Chapman, Wesley Truman Daniel, Mickey O’Sullivan, John Victor Allen, and James Errico. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies