By ArtiZen Editor

A chattering crow lives now nine generations of aged men,

but a stag’s life is four time a crow’s,

and a raven’s life makes three stags old,

while the phoenix outlives nine ravens,

but we, the rich-haired Nymphs

daughters of Zeus the aegis-holder,

outlive ten phoenixes.

——Greek Literature,Precepts of Chiron

The self-renewing bird is one of our most enduring myths.

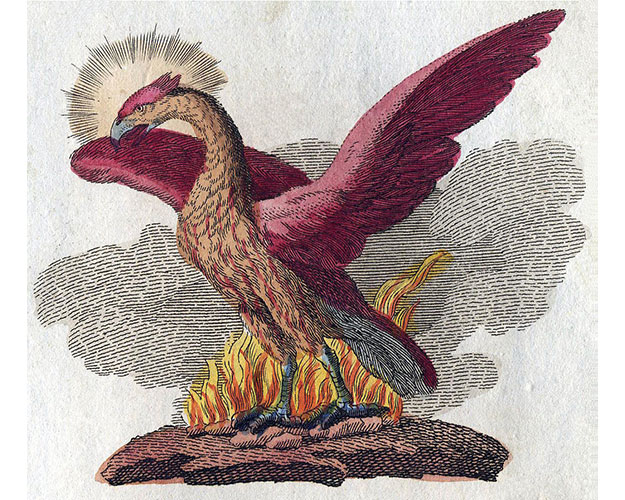

The Phoenix, a mythical bird, associated with the sun, originated from Egyptian mythology and later became a prominent figure in Greek, Roman, and Christian cultures. It symbolizes rebirth, renewal, and immortality, often depicted as a beautiful, colorful bird that burns itself to ashes and then rises anew.

The origin of the phoenix has been attributed to Ancient Egypt by Herodotus and later 19th century scholars. Numerous influential historians and writers in Ancient Greek and Roman Empire have contributed to the retelling and transmission of the phoenix motif. Over time, extending beyond its origins, the phoenix could variously “symbolize renewal in general as well as the sun, time, the Roman Empire, metempsychosis, consecration, resurrection, life in the heavenly Paradise, Christ, Mary, virginity, the exceptional man, and certain aspects of Christian life.

The Greeks rooted the tale of the phoenix in Western imagination more than 2,500 years ago, but its story began in ancient Egypt and Arabia. The fabled bird is said to live 500 years or more, and when the old bird is tired, it flies from Arabia to land in Heliopolis, Egypt, the “City of the Sun.” There, it gathers cinnamon twigs and resin to build a nest of spices atop the Temple of the Sun. The sun ignites the nest and the old phoenix dies in flames. A new, young phoenix emerges from the ashes and wings back to Arabia to live another life cycle. The bird’s features have changed over the centuries, but most agree it’s an eagle-like bird with shining red, golden, and purple plumes.

The phoenix is often depicted in ancient and medieval literature and medieval art endowed with a halo, emphasizing the bird’s connection with the Sun. Some said that the bird had peacock-like coloring, and Herodotus’s claim of the Phoenix being red and yellow is popular in many versions of the story on record. Herodotus, Pliny, Solinus, and Philostratus describe the phoenix as similar in size to an eagle. Purportedly, phoenix appears in the earthly world every 500 years, and it often showed up in great years of history.

Romans loved the phoenix. Their coins showed the emperor’s head on one side and the phoenix on the other. “The phoenix represented Rome itself, the eternal nature of the empire, that it continues to return with each new emperor,” Nigg says.

But even as Rome began its decline, the phoenix flourished in early Christian Europe. Its message of rebirth and eternal life fit Christian themes, and popes like St. Clement (96 AD) used the phoenix to prove Jesus’s resurrection. Monks included phoenixes in the bestiaries of the Middle Ages, making no distinction between God’s wondrous creations—real or imaginary. During the Renaissance, the phoenix was a popular emblem of royals like Elizabeth I and martyrs like Joan of Arc. “This is the greatest period for the phoenix,” according to Nigg. “Why not? With a word like ‘renaissance,’ a time of rebirth and learning, you definitely have his time.”

Legendary birds around the world are often linked to the phoenix, including what Nigg calls “phoenix counterparts” such as the Persian Simurg, Chinese Feng Huang, and Russian firebird (Zhar-ptitsa). These birds arose from their own local folklore.

The Chinese phoenix Feng Huang (Ho-o in Japan) is an entirely separate bird dating back at least 7,000 years. Even though the Eastern bird has no fire, never dies (so is never reborn), and looks like a pheasant. Its very name represents the union of yin-yang, with “feng” being male and “huang” female. When paired with a dragon, the phoenix represents the empress and the dragon the emperor. This auspicious pairing also symbolizes good luck and harmony between husband and wife.

The ancient Greeks believed in a process called “the transmigration of the soul” or metempsychosis believing that after death, a person’s soul could be transmigrated into another being such as another human baby, an animal or even an inanimate such as a tree or plant. This idea of the eternal nature of the soul is common to many religions such as Christianity, Hindus, Druids Celts, and many indigenous people such as Australian Aborigines and native Americans.

In Native American culture, the phoenix was called the Thunderbird and it was a large, colourful bird that could affect the weather. It also had healing powers not only for humans but by regenerating the earth by bringing rain. A phoenix was also the first image depicted on the Great Seal of the newly reborn United States of America in 1782 after the war of independence from Britain. It was replaced later by that of an eagle which had become an American symbol.

Whatever the phoenix is, it is an enduring symbol of hope and regeneration, giving humanity the chance to shake off their old life and begin again with a new one, renewed in energy and outlook, with the physical advantages of youth, and the wisdom from having lived a thousand lives.

Reference:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phoenix_(mythology)

https://phoenixcreativearts.co.uk/the-legend-of-the-phoenix

https://www.swarthmore.edu/bulletin/archive/wp/october-2008_the-phoenix-through-the-ages.html