By Daniel McCoy

The first systems of writing developed and used by the Norse and other Germanic peoples were runic alphabets. The runes functioned as letters, but they were much more than just letters in the sense in which we today understand the term. Each rune was an ideographic or pictographic symbol of some cosmological principle or power, and to write a rune was to invoke and direct the force for which it stood. Indeed, in every Germanic language, the word “rune” (from Proto-Germanic *runo) means both “letter” and “secret” or “mystery,” and its original meaning, which likely predated the adoption of the runic alphabet, may have been simply “(hushed) message.”

Each rune had a name that hinted at the philosophical and magical significance of its visual form and the sound for which it stands, which was almost always the first sound of the rune’s name. For example, the T-rune, called *Tiwaz in the Proto-Germanic language, is named after the god Tiwaz (known as Tyr in the Viking Age). Tiwaz was perceived to dwell within the daytime sky, and, accordingly, the visual form of the T-rune is an arrow pointed upward (which surely also hints at the god’s prominent role in war). The T-rune was often carved as a standalone ideograph, apart from the writing of any particular word, as part of spells cast to ensure victory in battle.

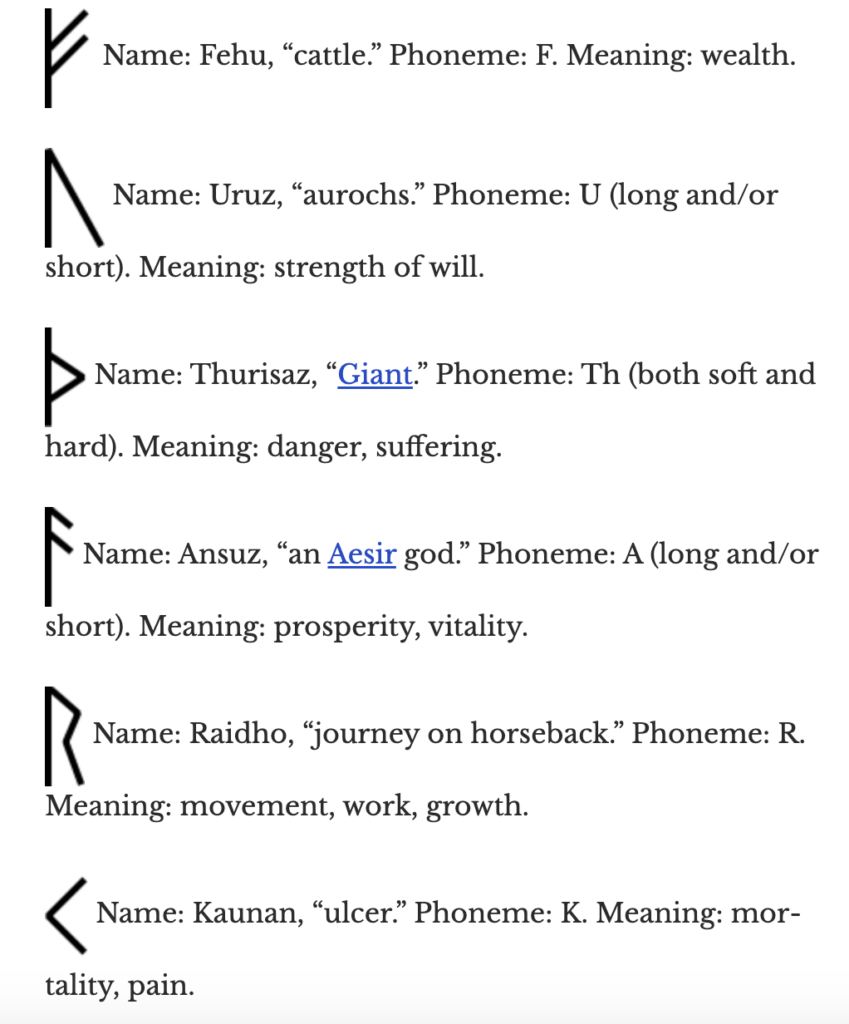

The runic alphabets are called “futharks” after the first six runes (Fehu, Uruz, Thurisaz, Ansuz, Raidho, Kaunan), in much the same way that the word “alphabet” comes from the names of the first two Semitic letters (Aleph, Beth). There are three principal futharks: the 24-character Elder Futhark, the first fully-formed runic alphabet, whose development had begun by the first century CE and had been completed before the year 400; the 16-character Younger Futhark, which began to diverge from the Elder Futhark around the beginning of the Viking Age (c. 750 CE) and eventually replaced that older alphabet in Scandinavia; and the 33-character Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, which gradually altered and added to the Elder Futhark in England. On some inscriptions, the twenty-four runes of the Elder Futhark were divided into three ættir (Old Norse, “families”) of eight runes each, but the significance of this division is unfortunately unknown.

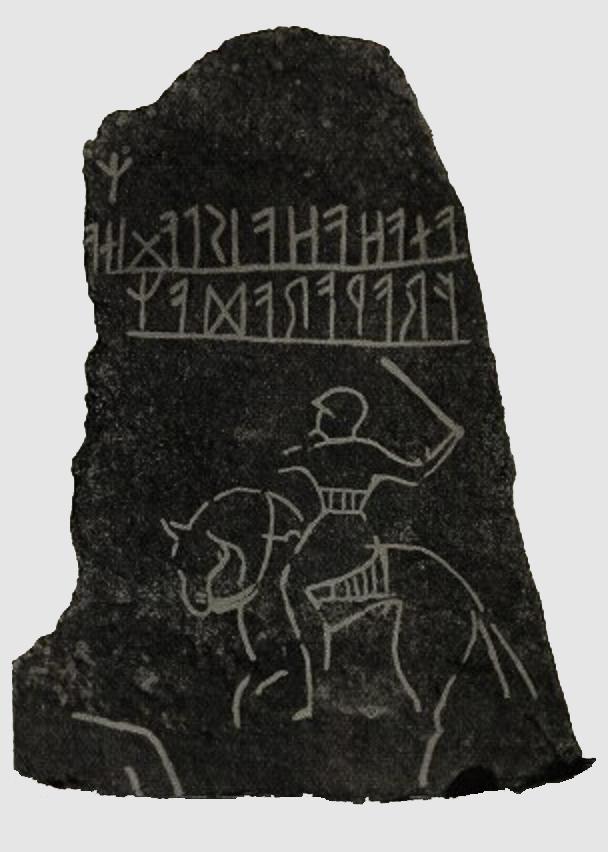

Runes were traditionally carved onto stone, wood, bone, metal, or some similarly hard surface rather than drawn with ink and pen on parchment. This explains their sharp, angular form, which was well-suited to the medium.

Much of our current knowledge of the meanings the ancient Germanic peoples attributed to the runes comes from the three “Rune Poems,” documents from Iceland, Norway, and England that provide a short stanza about each rune in their respective futharks (the Younger Futhark is treated in the Icelandic and Norwegian Rune Poems, while the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc is discussed in the Old English Rune Poem).

THE ORIGINS OF THE RUNES

While runologists argue over many of the details of the historical origins of runic writing, there is widespread agreement on a general outline. The runes are presumed to have been derived from one of the many Old Italic alphabets in use among the Mediterranean peoples of the first century CE, who lived to the south of the Germanic tribes. Earlier Germanic sacred symbols, such as those preserved in northern European rock carvings, were also likely influential in the development of the script.

The earliest possibly runic inscription that we know of is found on the Meldorf brooch, which was manufactured in the north of modern-day Germany around 50 CE. The inscription is highly ambiguous, however, and scholars are divided over whether its letters are runic or Roman. The earliest unambiguous runic inscriptions are found on the Vimose comb from Vimose, Denmark and the Øvre Stabu spearhead from southern Norway, both of which date to approximately 160 CE. The earliest known carving of the entire futhark (alphabet), in order, is that on the Kylver stone from Gotland, Sweden, which dates to roughly 400 CE.

The transmission of writing from southern Europe to northern Europe likely took place via Germanic warbands, the dominant northern European military institution of the period, who would have encountered Italic writing firsthand during campaigns amongst their southerly neighbors. This hypothesis is supported by the association that runes have always had with the god Odin, who, in the Proto-Germanic period, under his original name *Woðanaz, was the divine model of the human warband leader and the invisible patron of the warband’s activities. The Roman historian Tacitus tells us that Odin (“Mercury” in the interpretatio romana) was already established as the dominant god in the pantheons of many of the Germanic tribes by the first century. Whether the runes and the cult of Odin arose together, or whether the latter predated the former, is of little consequence for our purposes here. As esteemed Indo-European scholar Georges Dumézil notes:

If Odin was first and always the highest magician, we realize that the runes, however recent they may be, would have fallen under his sway. New and particularly effective implements for magic works, they would become by definition and without contest a part of his domain. … Odin could have been the patron, the possessor par excellence of this redoubtable power of secrecy and secret knowledge, before the name of that knowledge became the technical name of signs both phonetic and magic which came from the Alps or elsewhere, but did not lose its former, larger sense.

From the perspective of the ancient Germanic peoples themselves, however, the runes came from no source as mundane as an Old Italic alphabet. The runes were never “invented,” but are instead eternal, pre-existent forces that Odin himself discovered by undergoing a tremendous ordeal. This tale has come down to us in the Old Norse poem Hávamál (“The Sayings of the High One”):

I know that I hung

On the wind-blasted tree

All of nights nine,

Pierced by my spear

And given to Odin,

Myself sacrificed to myself

On that pole

Of which none know

Where its roots run.No aid I received,

Not even a sip from the horn.

Peering down,

I took up the runes –

Screaming I grasped them –

Then I fell back from there.

The tree from which Odin hangs himself is surely none other than Yggdrasil, the world-tree at the center of the Germanic cosmos whose branches and roots hold the Nine Worlds. Directly below the world-tree is the Well of Urd, a source of incredible wisdom. The runes themselves seem to have their native dwelling-place in its waters. This is also suggested by another Old Norse poem, the Völuspá (“Insight of the Seeress”):

There stands an ash called Yggdrasil,

A mighty tree showered in white hail.

From there come the dews that fall in the valleys.

It stands evergreen above Urd’s Well.From there come maidens, very wise,

Three from the lake that stands beneath the pole.

One is called Urd, another Verdandi,

Skuld the third; they carve into the tree

The lives and fates of children.

These “three maidens” are the Norns, and their carvings surely consist of runes. We therefore have a clear association between the Well of Urd, the runes, and magic – in this case, the ability of the Norns to carve the fates of all beings.

Presumably, then, after Odin discovered the runes by ritually sacrificing himself to himself and fasting for nine days while staring into the waters of the Well of Urd, it was he who imparted the runes to the first human runemasters. His paradigmatic sacrifice was likely symbolically imitated in initiation ceremonies during which the candidate learned the lore of the runes,[18][19] but, unfortunately, no concrete evidence of such a practice has survived into our times.

RUNIC PHILOSOPHY AND MAGIC

In the pre-Christian Germanic worldview, the spoken word possesses frightfully strong creative powers. As Scandinavian scholar Catharina Raudvere notes, “The pronouncement of words was recognized to have a tremendous influence over the concerns of life. The impact of a sentence uttered aloud could not be questioned and could never be taken back – as if it had become somehow physical. … Words create reality, not the other way around.” This is, in an important sense, an anticipation of the philosophy of language advanced by the twentieth-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger in his seminal essay Language. For Heidegger, language is an inescapable structuring element of perception. Words don’t merely reflect our perception of the world; rather, we perceive and experience the world in the particular ways that our language demands of us. Thinking outside of language is literally unthinkable, because all thought takes place within language – hence the inherent, godlike creative powers of words. In traditional Germanic society, to vocalize a thought is to make that thought part of the fabric of reality, altering reality accordingly – perhaps not absolutely, but in some important measure.

Each of the runes represents a phoneme – the smallest unit of sound in a language, such as “t,” “s,” “r,” etc. – and as such is a transposition of a phoneme into a visual form.

Most modern linguists take it for granted that the relationship between the signified (the concrete reality referred to by a word) and the signifier (the sounds used to vocalize that word) is arbitrary. However, a minority of linguists embrace an opposing theory known as “phonosemantics:” the idea that there is, in fact, a meaningful connection between the sounds that make up a word and the word’s meaning. To put this another way, the phoneme itself carries an inherent meaning. The meaning of the word “thorn,” for example, derives in large part from the combined meaning of the phonemes “th,” “o,” “r,” and “n.”

The phonosemantic view of language is in agreement with the traditional northern European view, where “words create reality, not the other way around.” The runes, as transpositions of phonemes, bring the inherent creative powers of speech into a visual medium. We’ve already noted that the word “rune” means “letter” only secondarily, and that its primary meaning is “secret” or “mystery” – the mysterious power carried by the phoneme itself. We must also remember the ordeal Odin undertook in order to discover the runes – no one would hang from a tree without food or water for nine days and nights, ritually wounded by his own spear, in order to obtain a set of arbitrary signifiers.

With the runes, the phonosemantic perspective takes on an additional layer of significance. Not only is the relationship between the definition of a word and the phonemes that comprise it inherently meaningful – the relationship between a phoneme and its graphic representation is inherently meaningful as well.

Thus, the runes were not only a means of fostering communication between two or more humans. Being intrinsically meaningful symbols that could be read and understood by at least some nonhuman beings, they could facilitate communication between humankind and the invisible powers who animate the visible world, providing the basis for a plethora of magical acts.

In the verses from the Völuspá quoted above, we see that the carving of runes is one of the primary means by which the Norns establish the fate of all beings (the other most often-noted method being weaving). Given that the ability to alter the course of fate is one of the central concerns of traditional Germanic magic, it should come as no surprise that the runes, as an extremely potent means of redirecting fate, and as inherently meaningful symbols, were thereby inherently magical by their very nature. This is a controversial statement to make nowadays, since some scholars insist that, while the runes may have sometimes been used for magical purposes, they were not, in and of themselves, magical.

But consider the following episode from Egil’s Saga. While traveling, Egil eats a meal with a farmer whose house is on the Viking’s route. The farmer’s daughter is dangerously ill, and he asks Egil for help. When Egil examines the girl’s bed, he finds a whalebone with runes carved on it. The farmer explains to Egil that these runes were carved by the son of a local farmer – presumably an ignorant, illiterate person whose knowledge of the runes could have only been flimsy at best. Egil, being a master of runic lore, readily discerns that this inscription is the cause of the girl’s woes. After destroying the inscription by scraping the runes off into the fire and burning the whalebone itself (!), Egil carves a different message in different runes so as to counteract the malignancy of the earlier writing. After this has been accomplished, the girl recovers.

We can see from this incident that the heathen northern Europeans made a sharp distinction between the powers of the runes themselves, and the uses to which they were put. While the body of surviving runic inscriptions and literary descriptions of their use definitely suggest that the runes were sometimes put to profane, silly, and/or ignorant purposes, the Eddas and sagas make it abundantly clear that the signs themselves do possess immanent magical attributes that work in particular ways regardless of the intended uses to which they’re put by humans.

THE MEANINGS OF THE RUNES