by Johnny Levanier

In a time when audiences were racing in droves to catch the latest talkie and hand-drawn animation was just finding its legs, a new medium brought kids (and adults, let’s be honest) back to reading. Comic books began as a dime-store novelty, and since then, they have gone through countless transformations, artistic explorations, public excises, declines and revivals.

The history of comic book styles is one as dynamic as the stories they contain, shaped not only by the hands of countless writers and artists but by millions of readers across nearly a century. While there might not be any mutants or doomsday weapons in the actual history of comics, its panels are every bit as unpredictable.

The Golden Age (1938-1950)

–

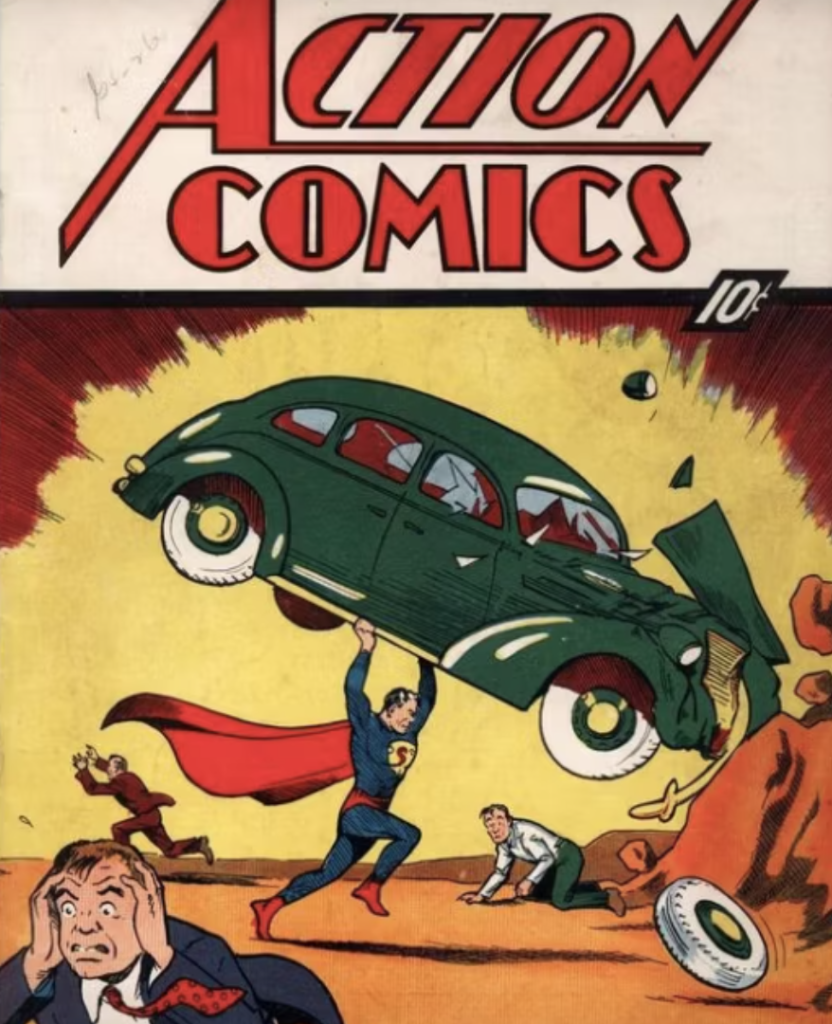

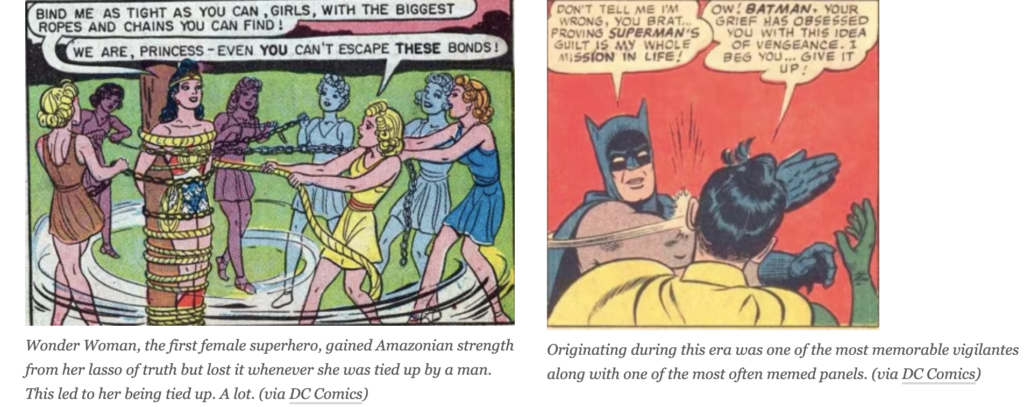

The Golden Age was truly an idyllic time. There was a clear stylistic distinction between good and evil, and superheroes were nothing more than happy-go-lucky do-gooders that battled and always defeated villains motivated by money or world domination. And that’s exactly why the comics of this age caught like wildfire. They fulfilled every kid’s dream of gaining larger-than-life powers, effortlessly overcoming their bullies and leaping out of their colorless neighborhoods into adventure.

Dropping literally out of the sky to kick off the Golden Age, Superman represents the comic book origin story. Newspaper comic strips (where the term ‘comic’ book comes from, incidentally) already existed along with radio shows featuring masked vigilantes like the Shadow. But Superman was the first super-powered musclehead to don a cape and skin-tight spandex to fight crime. Readers couldn’t take their eyes off of him. Superman set the tone for every superhero to come after, even becoming the first to earn his own exclusive comic book dedicated to his adventures in a time when characters were typically restricted to one-shot stories in variety publications.

Art styles of the Golden Age of comics

- Though printed in booklet form, comics did not deviate far from their newspaper ancestors, telling a straightforward story through basic sequential images.

- Cartooning was simple as publishers were not yet at the level of investing in or attracting serious artists.

- Panels were laid out in basic square grids, often full of more dialogue than imagery.

The Silver Age (1950-1971)

–

Not unlike the youth of its readers, the Golden Age was a time of whimsy and innocence that couldn’t last forever. Fans were growing up—some of them returning home from a horrific World War—and the idea of an invincible, caped avenger casually overcoming the world’s great evils became less and less convincing. These factors led to a decline in superhero stories and a rise in comic titles that would appeal to more adult sensibilities—the Silver Age of Comic Books.

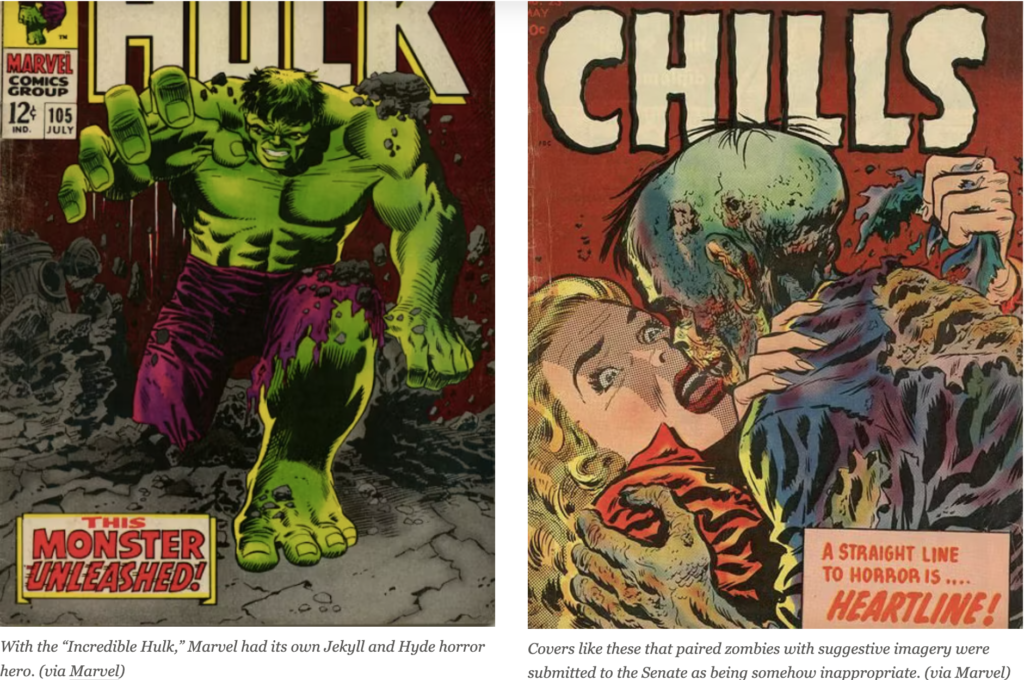

Publishers explored racier genres, and by far the most successful was horror. These gruesome tales single-handedly rescued the industry from its fate as a half-remembered fad, and their influence stretched beyond comics to likes of acclaimed film director John Carpenter. The visual styles mimed these darker themes, mixing in surrealistic and sometimes disturbing imagery.

These comic books were so effectively grisly that morality groups—already raging against comics as “junk food for the young mind”—now regarded them as the indisputable tools of the devil, despite the fact that majority of its readership was adults.

After a number Senate hearings, publishers created the Comics Code Authority (CCA), whose strict censorship forbade even the words “horror,” “terror” or “crime” in any titles. The result was a growing pains era of artistic experimentation, fast and loose writing and political suppression all rolled into one.

Art styles of the Silver Age of comics

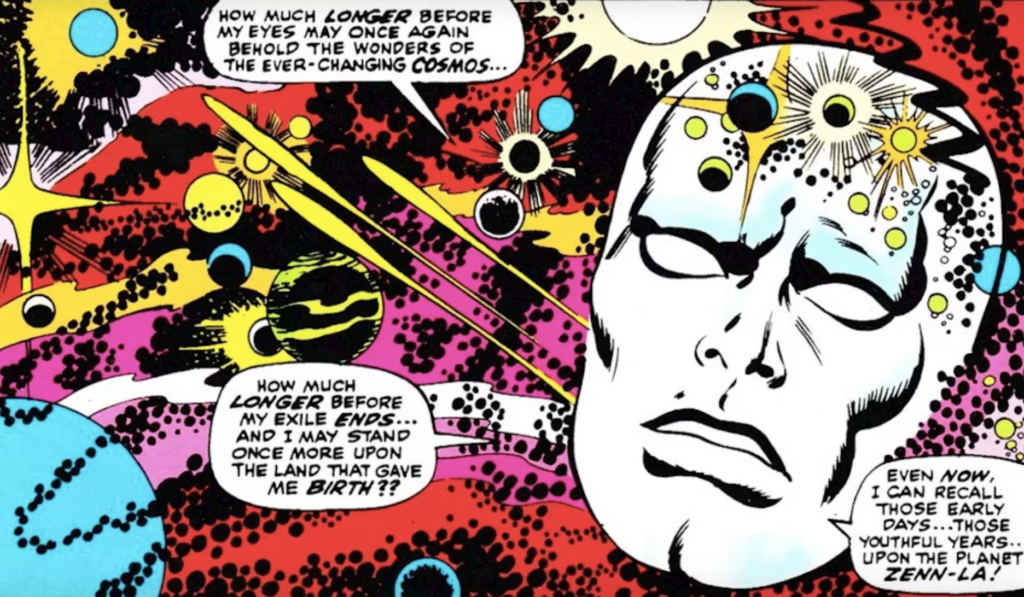

- Comics took their inspiration from art movements of the past, most notably surrealism, to illustrate the strange worlds in which their heroes lived.

- With comics now established as a lucrative medium, cover images relied less on cheap, attention-grabbing tactics and instead became an artistic representation of the issue’s themes or a protagonist’s state of mind.

- Comic books found true artistic expression for the first time in the Pop Art movement, which appropriated commercial objects such as product labels, magazine ads and comics for the purpose of fine art.

The Bronze Age (1971-1980)

–

As suggested by its name, the Bronze Age wasn’t as lustrous as the carefree Golden Age or the experimental Silver Age. Having exhausted just about every dastardly scheme a supervillain could hatch, comics gave its heroes even tougher enemies to confront.

It all began with a story in Spider-man in which the hero’s best friend suffers a drug overdose. Spider-man is helpless, and his alter ego, Peter Parker, has no choice but to take the stage, relying solely on his gifts of persuasion and empathy to save the day. The CCA opposed the inclusion of drug topics, whatever the message, but Marvel published the issue anyway with reader support. This caused the public to lose respect for the CCA and led to the end of censorship, paving the way for darker stories (more on that later).

Around this time, writer Chris Claremont revived a cancelled Silver Age series about a ragtag group of mutants called the X-men (heard of it?). Adding racially diverse, international characters to its cast, Claremont’s second wave of mutants still had godly powers, but now they were reviled by the public for that very reason. Echoing the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement, prejudice against the X-men’s genetic traits became the comic’s most enduring theme.

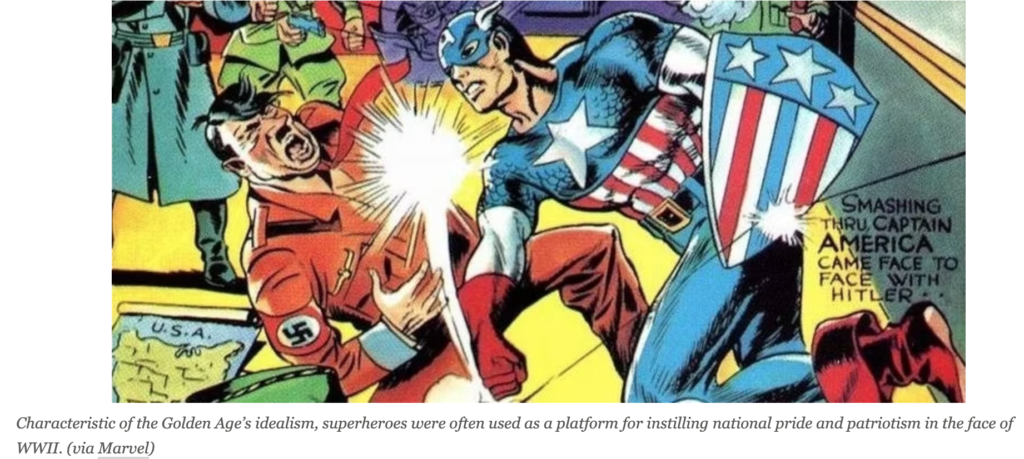

While the Golden Age portrayed social topics like World War in typical Golden Age fashion—unfailing virtue and easy justice—Bronze Age comics dealt with the gritty realities of urban life in ways that had no real answer. Maybe Captain America could smack Hitler in the face, but how does a superhero attack the intangible foes of bigotry and addiction?

As the stories became more focused around gritty, realistic stories, the style of the imagery morphed to match.

Art styles of the Bronze Age of comic books

- Comics traded in surrealism and experimentation for photorealistic depictions of the urban landscape.

- The alter-ego side of the superhero’s life is given more panel time, and sensational costumes took a backseat to depictions of everyday people.

- Depth of focus and lighting gave comics a cinematic style, heightening the reader’s emotional connection.

The Dark Age (1980-1993)

–

Unlike the actual Dark Ages, this era was where comic books achieved enlightenment. Until then, the Golden Age’s uncomplicated right and wrong still echoed (if just subtly updated to suit the times). Here, writers threw all of it out the window and showed us that a comic book hero’s world was just as gritty as the enemies he faced.

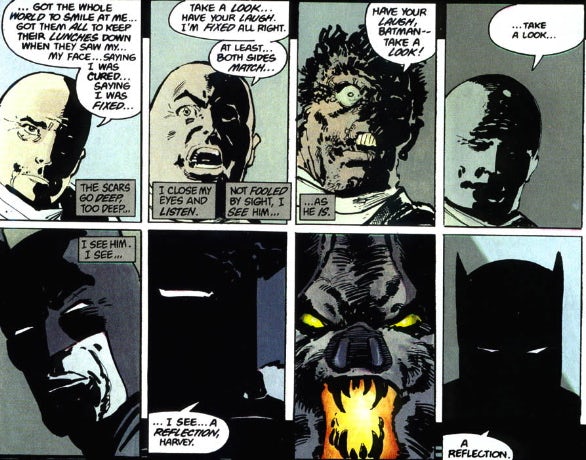

Stories like “The Dark Knight Returns” and “V for Vendetta” warned of an ominous future no amount of heroism could prevent. Writers crafted characters who were psychologically complex, often dangerously so. Alan Moore’s “The Killing Joke” introduced us to a Joker who was more than a giggling jester but a frighteningly psychotic serial killer. “Watchmen” gave us heroes that were pushed to questionable actions by the very nature of the world they were trying to defend. During this age, the line between hero and villain wasn’t just blurry; writers revealed that it never existed at all.

“The Killing Joke” paved the way for all future comic villains—ghoulish stalkers more intent on psychological torture than the hero’s death. (via DC Comics)

The Batman of years past was far removed from the haunted figure we know today, until “The Dark Knight Returns.” (via DC Comics)

Frank Miller’s version of Daredevil tackled more than costumed bad guys—he often found himself in a losing battle with the seediness of ordinary city crime. (via Marvel)

But it wasn’t all dark, even when it was. Independent publisher Image Comics was born, and their flagship hero, Spawn, received unprecedented popularity, enough to spawn (sorry!) a movie adaptation only a few years after its inception. This and several other popular titles such as “Prophet” and “The Savage Dragon” also spawned (last one, promise) more interest in creator-owned comics as a whole.

Ironically, as the imagery in these comics was becoming darker and more stylized—playing with lighting and deep, dark, contrasting colors—the genre was thrust out of the shadows of pulp and into the light of literary awareness. The idea of a sustained comic as a single work of literature led to the publication of several graphic novels, culminating in Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” the first comic series to win a Pulitzer Prize. Comic books were finally regarded as a legitimate art form, as malleable and open to creative expression as any medium.

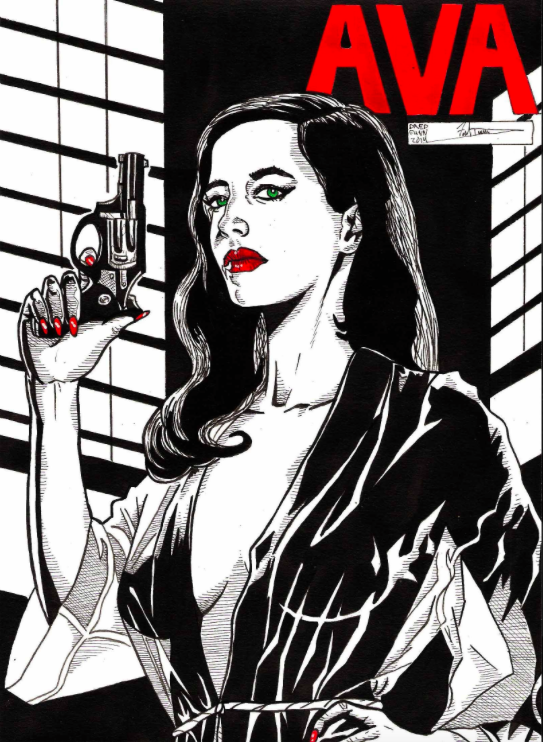

Sin City, the epitome of a dark comic, reinvented the crime noir tale with a style of detailed characters, minimal color and a world of ambiguous black and white shapes. (via Dark Horse)

Spawn is often depicted as entombed in his own costume—chains on his arms and his cape wrapping his body. (via Image Comics)

Art styles of the Dark Age of comics

- Night was the prominent setting for virtually all stories of this age, leading to an art style that favored strategic lighting and long shadows.

- Similarly, artists took their inspiration from hard-boiled noir films of the 40s and 50s, creating gloomy, dubious worlds of smoke, rain, alleyways and silhouettes.

- Silver Age horror comics influenced the Dark Age in a more psychological sense, with disturbing portraits and unnatural angles that created a perpetual sense of unease.

The influence of horror can be seen in Venom, with his unhinging jaw of razor teeth and body of black goo. (via Marvel)

In Spawn, comics literally went to hell, not surprising with character names like The Violator. (via Image Comics)

The Ageless Age (1993-Present Day)

–

We’ve now reached the point in our journey across many colorful panels at which there is no definitive way to categorize the present “age.” Comics have expanded into something without shape or borders—a nebulous mass of nerd wonder.

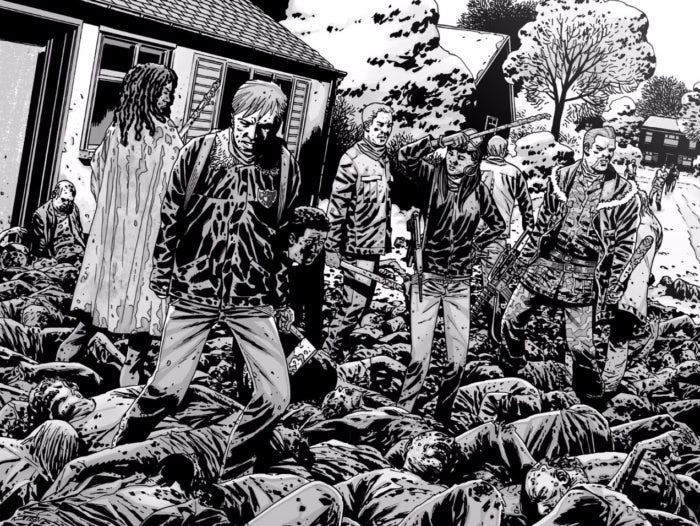

Advanced technology in film, television and video games has created an unstoppable juggernaut of adaptations, leading to an upsurge in comic book readers from all walks of life. Plus, the impact of Image Comics is still being felt, as readers continue their interest in indie books fueled by the industry’s rampant commercialization. No longer restricted to publishing giants Marvel and D.C., writers are free to explore specialty publishers and niche markets, even foregoing traditional distribution channels by publishing their content on the internet.

One thing can be said about our current comic book age: it’s a time when the superhero doesn’t have to be heroic or dark or even present at all. Comic books can be as pulpy or as serious or as just plain weird as you want them to be. Like the invincible Superman of the optimistic Golden Age, now is a time when anything is possible.

Art styles of the Ageless Age of comics

- Advanced technology has led to creative illustrative techniques—everything from digital painting to 3D modeling.

- The line between film and comic is now so thin that some series are adapted into motion comics, adding voice actors and animation to the panels with no change to the art itself.

- The ubiquity of publishers has led to a wide variety of art styles. Design now varies drastically, depending on the nature of the comic and the choices of the creator (rather than the uniform “in-house” styles of the past).

In “Black Hole,” a group of teenagers contract a mutating virus. This pivotal comic traces their path through heartbreak and alienation with enough horror imagery to make David Cronenberg flinch. (via Fanta Graphics)

“Scott Pilgrim” is a combination of many things dear to the heart of nerds everywhere: manga art, comic storytelling and video game action. (via Oni)

Like “Sin City,” “100 Bullets” took crime comics to new heights with episodic narratives intricately interwoven over its 100 issue run. (via Vertigo)

In “Y the Last Man,” every person with a Y chromosome (that is, all of the men) are killed by a mysterious virus—except one. This comic invited readers to consider how a society that favors men might crumble, if they all just up and died. (via Image Comics)

Comic books have had a long and vibrant history—far too long to represent in one modest article. The references here represent but a handful of pivotal moments as well as some of my personal favorites. Maybe I missed yours.