Ask almost any new writer to tell you about their story idea…. And something profound will happen

The story is immediately transfigured, the majestic, beautiful, articulate thing in their head is… now a rambling, thirteen-page dissertation on every character, their backstories, and the entire history of the made-up world. It’s no secret that ideas-especially ideas as expansive as the ones we make up for our fiction are messy things.

Most of the work writers do is just making sense of it all. Thus, we end up with the CSI-style red-yarn pin maps, the avalanches of notecards, and the labyrinthine folders of text documents.

But what if I told you it could be simpler than that?

What if I told you that you could fit the entire thing…. into one of these?

Today’s herculean trial of a question comes from our lovely patron, who asks: what are some tips for outlining multi-chapter-long fiction. It sounds like a simple question. But many methods that some experts talked about were template after template, an endless deluge of suggestions that you write a particular story structure.

Give your hero an opponent to spar with: give them a “darkest hour” before the climax, make sure they experience some kind of moral shift by the story’s end, and always follow the hero’s journey. Depending on the story you are writing, that stuff can be helpful… but it’s not outlining.

Outlines don’t tell you what to put into your story, they don’t make decisions for you, they don’t try to tell you what would be best, and outlines are for organizing your idea. They lend a shape to the chaos, they help you, the author, to understand…. So that you can write. And for that, I was able to find precious little, so, I did the only reasonable thing, and came up with a method of my own, or I didn’t come up with it so much as I stumbled upon it by working on a bunch of short stories in the past, but at least this way you know it has worked for someone. This is a Matryoshka or a “Russian Nesting Doll”, not much to look at on the surface; kind of a beautifully-painted wooden peanut, but crack it open, and you find what makes this little nick-knack so special: layers of layers of dolls inside. This one item is itself a collection.

A simple shape, easy to understand, but with a hidden depth. And because of the way it’s built, even when you take it apart and scatter the pieces, it’s still very clear how they all fit together. The shape of the top layer cascades down through the whole thing, allowing it all to assemble into one single, complete piece. And your story can do this too.

The trick is to view each piece of content as a potential layer, whatever you come up with, be it an event, a character, a setting, or an object, it is bound to be full of other materials.

So full, in fact, the problem comes full circle and you just end up lost in all the content within your content. In order to get that nice, cascading, self-contained matryoshka effect, you need some way to define the shape of your layers. Something consistent that works at both the largest and the smallest levels of your story. That something is a combination of concept and composition, applied to each piece of content individually. The content itself is the tangible material of your story- the stuff that can actually be experienced.

The concept, on the other hand, is the soul of the content. The abstract. Where we find the intent, the basic premise, and the theme of it. By comparison, the composition is the far more technical side of your content. This is your plan to execute how you intend to actually put material on the page. It’s also the function of your material in the story — What purpose it serves. Once you have a handle on both of these things for any one piece of content, you can use them as a guide to craft everything that exists within.

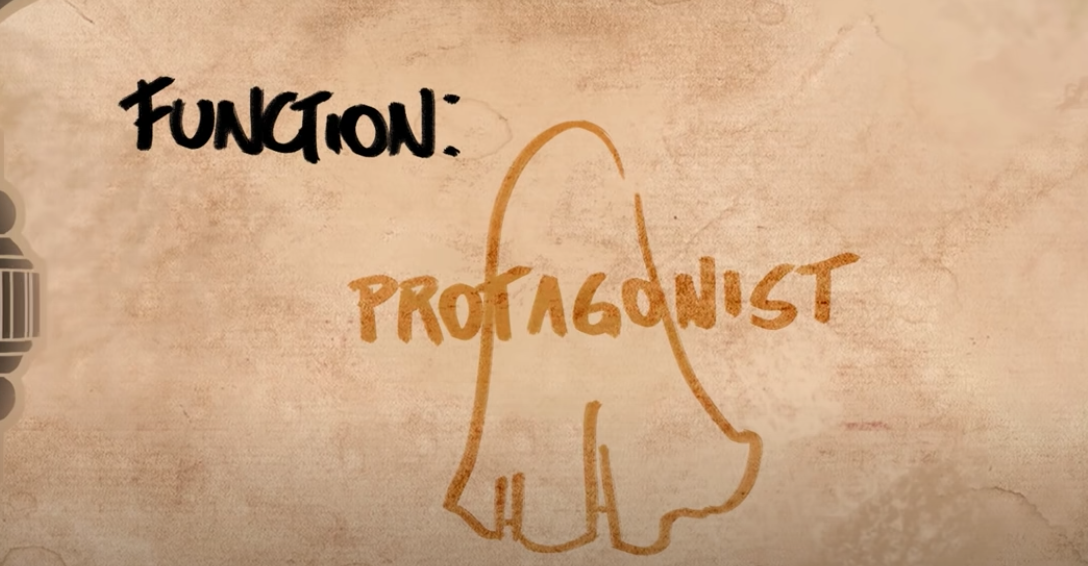

For a very simple example, let’s take a ghost for instance. A character, a piece of content. If we want to figure out all the content within our ghost, we’d start by developing a concept.

So, the first aspect of the concept: what’s our intent for this spirit? Let’s say we want it to do something good for a change. A well-meaning specter the audience can feel sympathy for.

Now the second aspect of the concept: what’s the basic premise? What’s the ghost about, what does it do? Maybe we want a ghost that says thwarts criminals?

To finish off our concept: what’s the theme within this ghost-what will unite all its contents?

Maybe vengeance, maybe everything about this ghost revolves around vengeance.

— -A good-hearted ghost that prevents crimes, driven by vengeance. We have a concept.

Now, how about that composition? We begin by asking: what’s the function of this ghost within our story? The protagonist, let’s say, and a perspective character, but not the only one. Now we ask how will we execute?

For this, we look back to our concept. If we want our ghost to be sympathetic, but also vengeful…. how about we hide the ghost’s motivation a little. We could do this by cutting back to the ghost’s perspective regularly for brief vignettes. But telling most of the story through the eyes of a murderer and a potential victim. Both are affected in strange ways by the ghost’s interference.

Okay, so we’ve got our piece of content, we’ve developed a concept for it, and we’ve figured out our composition. That makes one solid layer, What do we do with layers in Matryoshka dolls? We create more of them. And this is how the whole method pays off. All we have to do is look back at the layer we’ve just created, find anything concrete-characters, objects, settings, and events and list them out.

In this case, we’ve got: a murderer who the ghost interferes, a victim who the ghost protects, and a cause for vengeance. Notice, that we’re not taking the time to define what the ghost looks like or what its specific capabilities are yet. That’s because we’re following the shape of this layer, rather than just sprouting out, whatever comes to us. Remember, we could do that all day. Much of the point here is creating boundaries for our creative process and nesting the tiny details within the larger ones. That stuff will all develop later, but maybe not here, maybe not now. To actually make the next layer, pick any one piece of content here, develop the concept and the composition, and repeat what we just did with the ghost. Let’s take that “cause for vengeance” event from earlier.

The concept first: Our intent is for this event to vindicate our ghost; prove that their vengeance is justifiable and that their fury is righteous. Our premise is that they’re consumed by vengeance because they were murdered by a lover they trust implicitly, and the confusion of the betrayal left them trapped between life and death, rather than at peace. Thematically, this event is about betrayal and the breaking of a heart.

Now, composition: we can execute our premise by creating a love story between the murderer and new love interest, mirroring it with the relationship the murderer had with the ghost, and forcing murky memories to surface in our ghost’s mind, making sense of their purgatory and the anger they feel. The function this event serves will be a revelation to the audience — a twist that changes their perspective of the ghost from an apparition trying to destroy a blossoming romance, to a heart-broken specter trying to get justice and save another victim from the same fate. By developing these two aspects of this one piece of content, look how much we’ve learned about this story, how much more content we have access to.

The murder that started it all, the implicit trust, the broken heart, the setting between life and death, and on and on. All beautifully stored within this layer’s premise: the ghost is vengeful because they were murdered by a lover, and trapped between worlds as a result of the unresolved heartbreak. We don’t need to describe all the possible contents here and now, we don’t need to discuss the composition. All that stuff folds neatly into the premise of this layer we’ve created. Go down to the next layer for all the finer details. And thus we have a little tidy nesting doll.

Before you tell others this golden elixir of creative clarity, there are some caveats: First, what I’ve shown you here is a top-down approach, focused on making all the layers within a piece of content. You can also do it the opposite way, bottom-up, by starting with some trifling piece of content and building a larger layer to harbor it. Simply ask yourself, what character, event, object, or setting makes this piece of content significant, then take that thing and build it into a layer above that lone piece of content! You can go infinitely upward this way… although I wouldn’t recommend it, which brings to the second caveat: don’t do this forever.

If you find a piece of content that you’re straining to build into a layer — the concept and composition just isn’t coming to you, maybe leave it that way. Not every sock on the ground needs an explanation. And if you’re building bottom-up. No need to paint the stars in the heavens, once you find a layer that promises a story you can get behind, embrace it. Make that your top layer — you story layer — and let that piece of content be the axis of the project. This will almost always be your protagonist, but thinking this way leaves you open to the possibilities. Thirdly, the same pieces of content will pop up un multiple layer cascades. Allow this to happen, but keep track of it. Connect whose iterations, and make sure they sync up with one another. The different places they appear will show you the different sides of that content, and all the ways it’s significant to your story.

Finally, this video is to help you fold ideas into ideas, it’s a good way to simplify the whole process, how you understand it, and how you communicate, it’s not good for visualization. If you need to lay everything out cleanly, document it, and create reference points…. Well, this is where those red-yarn pin maps and note card palaces come back into the frame.