By John Staat and Collin Chambell@Polygon

When John Staats landed his first job in the game industry, he was surprised to learn he’d be working — in a central role — on one of the biggest games ever made. His new employer was Blizzard Entertainment, and this was early 2001.

The project was a top-secret MMO based on fantasy real-time strategy series WarCraft. Staats was hired to create the game’s dungeons. He understood, immediately, that the internally named World of Warcraft was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

As it turned out, his new education would be about more than texture-mapping and asset-placement. He was about to learn the value of creative chaos.

A SHABBY OFFICE

Coming from a glitzy media career in Manhattan, Staats was initially disconcerted to find that World of Warcraft was being created in a shabby office where junk lay on the floors and line managers sat at hallway desks. He soon found out that the office’s motley collection of office chairs was both insufficient and variably functional. To avoid the constant peril of having his chair “filched” by a co-workers, he bought his own, distinctive executive chair.

But he was happy with his new, dream job. Staats had been a suit-wearing Madison Avenue mid-level advertising executive, earning a decent salary of $80,000. But he loved video games. In his spare time, he created highly detailed mods and levels for first-person shooters.

Back in New York, when he’d spotted that Blizzard, one of his favorite developers, was looking for designers, he’d applied. His portfolio of highly polished Quake levels impressed Blizzard’s creative leads — keenly so, it turned out, because they were struggling to find experienced talent — and so they hired him. He started on $50,000 a year, a significant cut in pay. He moved from the metropolitan expense of New York City life to the snowbird-fueled expense of Orange County, and began work.

EXTREMELY INFORMAL

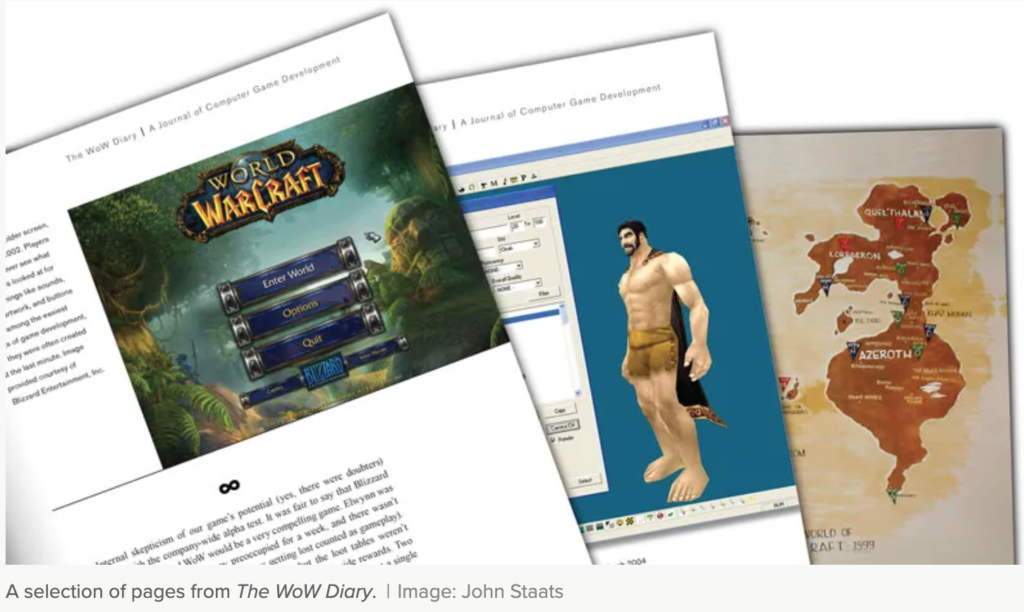

In his new book, based on personal diaries written at the time, Staats recalls his time at Blizzard, from the earliest days of WoW’s development, right up to the game’s launch in 2004. The WoW Diary is a good read, full of human, creative, and technical details of the game’s difficult gestation.

Certainly, there’s a sizable audience for Staats’ story. In 2018, The WoW Diary attracted almost $600,000 from 8,379 backers on Kickstarter. Video game books rarely sell more than a few hundred copies.

One of its main themes is how the early development effort was extremely informal. “The [development] area was a dump,” he writes in the book’s first chapter. “It was decorated like someone’s basement … Half the lights were burnt out. The closest thing to a kitchen was a tiny microwave next to a sink full of dishes. Food stains were ground into the carpet.”

This is a far cry from Blizzard’s modern offices which are stylish, spacious, well-lit, and festooned with expensive statues and artifacts. Blizzard’s modern success, its sumptuous riches, are paid for by World of Warcraft’s success, a game that has attracted more than 140 million players during its lifetime to date, grossed billions of dollars, and is currently enjoying a renaissance following the release of World of Warcraft Classic.

EXPERIMENTAL MODE

The original World of Warcraft was created by a team of 40 people, which eventually doubled in size as the launch drew close. By contrast, the current World of Warcraft development team numbers in the hundreds.

In 2001, Blizzard was already 10 years old, and a major player in the game industry. Blizzard enjoyed success through the ’90s with franchises like Diablo, StarCraft, and Warcraft. Inspired by the successes of Ultima Online, Lineage, and most especially the 3D MMO EverQuest, the company’s leaders decided to create a massively multiplayer game, in which players would adventure together and socialize.

A central theme in Staats’ book is how Blizzard’s leadership, led by Allen Adham, Frank Pierce, and Mike Morhaime, believed strongly in decentralized decision making, most especially when the company was in experimental mode.

“The structure was very flat,” Staats recalled, in a phone interview with Polygon. “Other companies are and were very hierarchical with lots of levels reporting to each other, and someone at the top with a driving vision, like an orchestra conductor. But there was no vision at Blizzard and very little structure. It had a jazz band kind of feel where everyone was just figuring stuff out together.”

In his book, Staats writes that Blizzard workers were “actually proud of the company’s founders.” He adds: “Hearing my teammates talk about [the founders] with enthusiasm was strange to me, coming from the politically charged atmosphere of Madison Avenue.”

FROM 2D TO 3D

The WoW Diary is a story of how the team worked its way through World of Warcraft’s fraught development, together, making it all up as they went along. As Staats points out at the start of his book, the company had no experience in making MMOs, and “zero experience” making 3D games.

In 2001, many game companies were struggling to manage the transition from 2D to 3D. They were desperately hiring people with 3D experience, and shedding developers who couldn’t make the leap. Most companies paid higher wages than Blizzard.

“We used to joke that they were just so cheap with everything,” said Staats. But he also acknowledges that the company was severely restricted. “Blizzard was owned by Vivendi at the time, which was a house of cards. There was no investment coming from Vivendi. Blizzard’s money went to Vivendi. We had to take out bank loans to pay for our own servers.”

Once he was fully integrated into the team, Staats learned that some of the situations that he’d initially viewed as being cheap, were actually smart. Seating the game’s producers in the hallway, rather than in their own offices, was a deliberate attempt to ease the flow of information among team members.

“By repeatedly inviting employees to give comments and suggestions, Blizzard’s leadership created an atmosphere where people felt comfortable giving opinions,” he writes. “This wasn’t easy to do because many in the company were introverted and reticent by nature. It took a proactive effort by management to foster a collaborative environment.”

Blizzard’s reliance on communal problem-solving came with its own costs though. Decision making took a long time, which translated into wasted expense and effort. The team often found themselves following blind alleys. “We made a lot of mistakes, and they all cost a lot of money,” he says.

TOOLS AND ENGINES

World of Warcraft was especially vulnerable to problems with well-worn tools and engines, which turned out to be flawed for MMO development.

“Technology was always a headache,” he writes, “which wasn’t surprising with something as complicated as an MMO.” Originally, the team worked on the same engine as its sister team, developing Warcraft 3, mainly as a matter of convenience and cost. But these were very different games. “It became apparent that re-using the Warcraft 3 engine wasn’t going to work.”

Blizzard made the decision to write a whole new engine. The solution turned out to be the right one, but at the time it was viewed as expensive and time-consuming. Thousands of labor hours were also lost when the team switched from creating art assets in Radion to 3D Studio Max. “There aren’t many developers, then or now, who were prepared to walk away from so much work that had already been done,” says Staats. “But that was always the Blizzard way. It was always about iteration, learning from mistakes and moving forward.”

MORALE ISSUES

The free-roaming nature of the project was not popular with everyone on the team, which led to severe morale issues. “A lot of people wanted structure,” recalled Staats in our interview. “They just wanted to be pointed in the right directions, and work 9 to 5.”

From the earliest days of development, long hours were the norm. Although Blizzard later enforced an anti-crunch policy, in which developers’ hours were limited, WoW’s designers and programmers regularly worked 60-hour weeks. After three years, the wear and tear started to show, particularly on the art team, who were required to churn out assets.

“When your routine is to come in and work on tree stumps, bushes, fences, and houses and you’re just doing this, day after day, year after year, it becomes really old, especially when there’s just no end in sight,” Staats said.

Despite grumbling and tiredness, he said that most of the team were fully committed to the game. “I didn’t have a life outside Blizzard,” he recalled. “It felt natural to come in on the weekends and to work late nights. A lot of us just loved the game, and the work we were doing.”

Staats believes that World of Warcraft’s success wasn’t based on the intellectual property (its main rival, in the early days, was Star Wars Galaxies), nor on any grand vision, and certainly not on generous funding. He said a company-wide disdain for marketing-led processes and the vision thing, allowed for free creativity. “Game designers should build from solid moment-to-moment gameplay,” he writes, “discovering where it leads them, instead of working backwards and forcing a vision to happen. The wrong approach is starting with a cool concept, and shoehorning it into the game.”

Blizzard’s free-for-all approach had its downsides, but it certainly achieved its goals. The team was allowed and encouraged to individually solve hundreds of tiny little problems over a period of years, until the game came to fruition.

In his book’s conclusion, Staats writes that World of Warcraft was “never a game with innovative technology or unique features,” but a gestalt of “meaningful and elegant systems” that were painfully attained, but that allowed players to enjoy an MMO of extraordinary depth and longevity.