By The Art Story

With soaring vaults and resplendent stained glass windows, Gothic architecture attempted to recreate a heavenly environment on earth. Elaborating on Romanesque styles, Gothic builders, beginning in the 12th century, further developed the use of flying buttresses and decorative tracery between stained glass windows thus creating interior spaces that dwarfed worshippers and dazzled their senses. Additionally, in response to a new interest in humanism (manifested later and powerfully in Renaissance Humanism), architectural and portable sculpture primarily depicted figures that acquired more naturalistic and sensuous features than had previously existed in the Middle Ages. Wealthy noblemen commissioned sumptuous manuscript illuminations, and toward the end of the Gothic era in the 14th century, elaborate altarpieces and frescoes became more common in churches and chapels.

Renaissance artists and writers in the 16th century coined the term Gothic, and the early art historian Giorgio Vasari infamously reinforced the unfavorable connotations when he referred to Gothic art as “monstrous and barbaric” since it did not conform to classical ideals. It was not until the mid-1700s with the Gothic Revival in England that the style shed its negative associations. Subsequently Gothic architecture in particular inspired new churches in the 19th century, city buildings, and university architecture well into the 20th century.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The innovations of Gothic architecture were premised on the ideas developed by Abbot Suger that earthly light contained divine light and that the physical edifice of the church needed to make this concept tangible. Revolutionary transformations of flying buttresses and groin vaulting allowed the inclusion of more stained glass windows in the church’s structure, thus transforming the everyday sunlight into a prism of colors that danced over the surfaces of the stone and reminded worshippers of God’s divine presence.

- A renewed interest in humanism, which had a slightly different cast than the later humanism of the Renaissance, led to more naturalistic figurative sculpture that decorated the exterior of the churches and housed sacred relics, which were increasingly important to a city’s reputation. In particular, representations of the Virgin Mary and Christ child move away from massive frontal poses to more typical, or everyday, poses that register the tender human emotion one often sees between mother and child.

- Combining aspects of Byzantine and Romanesque styles and even borrowing from Islamic architecture, Gothic art and architecture revel in its eclectic roots, growing and morphing to suit regional tastes and tendencies. By the end of the Middle Ages, the Gothic style had become “international” in its spread across Europe, and its emphasis on naturalism sparked the revolution in painting that flourished during the Renaissance even if its architecture was replaced with straighter lines and classical proportions.

Beginnings of Gothic Art and Architecture

The Gothic Era

City-states and feudal kingdoms dotted Europe, and the power of the Catholic church continued to grow during the Gothic era. With increasing prosperity and more stable governments, cultural changes included the early formations of universities, like the University of Paris in 1150, and the proliferation of Catholic orders, like the Franciscan and Dominicans. The monks and theologians ushered in a new Humanism that sought to reconcile Platonic ideals and Church theology. The humanism at this time saw man as part of a complex hierarchy, divinely ordered by God whose ultimate nature surpassed reason.

Increasing trade led to the growth of many urban centers, and the local Cathedral became a sign of civic pride. At the same time, noble patronage began to play a primary role in building projects, as stained glass windows and portals emphasized the identification of the king as a kind of earthly representation of divine authority, as seen in the “royal portal” reserved for nobility and high ranking church officials. Some Gothic churches took decades to build, contributing both to the town’s economy and to the expansion of the necessary guilds that represented the various trades involved in construction and design. Most of the Early Gothic architects, sculptors, and designers of stained glass windows were anonymous, and it is only later in the High Gothic period that architects and artists known as “masters” became identified.

The architecture that informed the Gothic period drew upon a number of influences, including Romanesque, Byzantine, and Middle Eastern.

Romanesque

Romanesque churches from the 10th to the 12th centuries are noted for their use of barrel vaults, rounded arches, towers, and their thick walls, pillars and piers. Housing the relics of saints, the churches were part of the pilgrimage routes that extended throughout Europe, as the faithful visited the holy sites to seek forgiveness for their sins and attain the promise of Heaven.

Gothic architecture retained the Romanesque western façade as the entrance to the church with its two towers, three portals and sculptural works in the tympanum, a half circle area above the door, as well as its cruciform plan. While Gothic churches continued the religious tradition of the pilgrimage path, their new style reflected a new economic and political reality.

The Pointed Arch and Middle Eastern Architecture

The pointed arch was a noted element of Middle Eastern architecture beginning in the 7th century, as seen in the Al-Aqsa Mosque (780) in Jerusalem. Widely deployed in the building of mosques and palaces like the fortress of Al-Ukhaidir (775), the pointed arch was found throughout the Middle East, North Africa, Andalucia (modern day Spain), and Sicily. As architectural critic Jonathan Meades wrote, these early examples “would in the 12th century become the quintessential architecture of Christendom.” As the Pope and Catholic rulers sought to extend the range of Christianity in the Middle Ages through the Crusades, knowledge of Middle Eastern architecture became more common among Europeans.

The pointed arch made the Gothic style possible, as it could be used for asymmetrical spaces and to intersect columns at a sharp angle thus displacing the weight into the columns and lightening the walls. The structure also became key to a number of subsequent Gothic innovations, including the lancet arch, creating a high, narrow, and steeply pointed opening; the equilateral arch, widening the arch to allow for more circular forms in stained glass; and the flamboyant arch, primarily used in windows and traceries for decorative effect.

Flying Buttresses and Byzantine Architecture

The flying buttress was used in a few important and influential Byzantine structures. The buttress employed a massive column or pier, situated away from the building’s wall, and a “flyer,” an arch that, extending from the wall to the pier, displaced the weight-bearing load from the wall. The Basilica of San Vitale (547) in Ravenna, Italy, pioneered an early use of the flying buttress. The Basilica was famous for its mosaics and was a powerful symbol of the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Empire before it. As a result, it became a model for later architecture. The Emperor Charlemagne, who established the Holy Roman Empire in 799 and was dubbed “the father of Europe,” designed his Palatine Chapel in Aachen, Germany, after the Basilica of San Vitale.

Early Gothic: Basilica of Saint-Denis (1144)

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (1135-1144), near Paris, pioneered the Gothic style. Abbot Suger led the rebuilding of the church, a venerated site where Saint Denis was martyred and where almost every French monarch since the 7th century had been buried. A noted scholar, friend, and advisor to King Louis VI and then Louis VII, Suger was influenced by the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Aeropagite, a 5th-6th century Christian philosopher and mystic. Pseudo-Dionysius believed that any aspect of earthly light was an aspect of divine light, a belief with which Suger concurred. Suger felt that the new Gothic style would lift up the soul to God. His design envisioned a soaring verticality, and key to this was the use of the pointed arch that allowed for a vaulted ceiling and thinner walls that could contain numerous stained glass windows. The Church of Saint-Denis became the model for the Gothic style of architecture, spreading throughout Europe.

Following on and expanding the Romanesque practice, Early Gothic churches also employed sculpture to decorate the building. Religious scenes were carved into the tympanum over the doorways, and the surrounding archivolts and lintels were filled with figures. Secular images were also created, as the Basilica of St. Denis had the signs of the zodiac carved into the sides of the left portal and scenes depicting the agricultural labors of the month on the right. Most noted were the various column statues, depicting Old Testament Kings and Prophets on the portal columns.

High Gothic (1200-80)

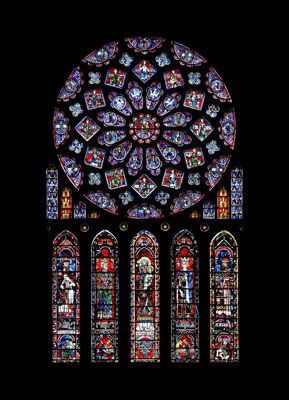

Beginning around 1200, the High Gothic period developed toward ever-greater verticality by including pinnacles, spires, and emphasizing both the structural and decorative effect of flying buttresses. The rose window was expanded in size, and the tracery, the intervening metal bars between sections of stained glass, was elaborated for decorative effect. Chartres Cathedral (1194-1420), Amiens Cathedral (1220-1269), and Notre Dame de Paris (1163-1345) were all notable examples of High Gothic. The High Gothic period was also marked by the development of two distinct sub styles: the Rayonnant and the Flamboyant. Most Late Gothic architecture employed the Flamboyant Style, which continued into the 1500s.

High Gothic churches continued to use sculptures, particularly around the portals, but figurative treatments became more naturalistic, as the figures stepped free of the columns that once contained them. Smaller, portable sculptures, like The Virgin and Child from the Sainte-Chappelle (c. 1260-1270), became popular. The small work, though elegant and stylized, is naturalistically sculpted, depicting the s-curve of movement and the realistic flow of draperies.

International Gothic

The International Gothic style is the term used for the courtly decorative style of illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, painting, and sculpture that developed around 1375. The style, associated with European courts, has also been called “the beautiful style,” for its emphasis on elegance, delicate detail, soft facial expressions, and smooth forms. The Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV in Prague, the Valois King of France, and the Visconti of Milan were the most important patrons and competed with each other to create a cultural capital that would attract leading artists. The portability of many of the works created, as well as the system of patronage that led artists to travel to different courts, spread the style’s influence throughout Europe.

Source from: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/gothic-art-and-architecture