Taking a deeper look at a little-known part of Getty’s collections

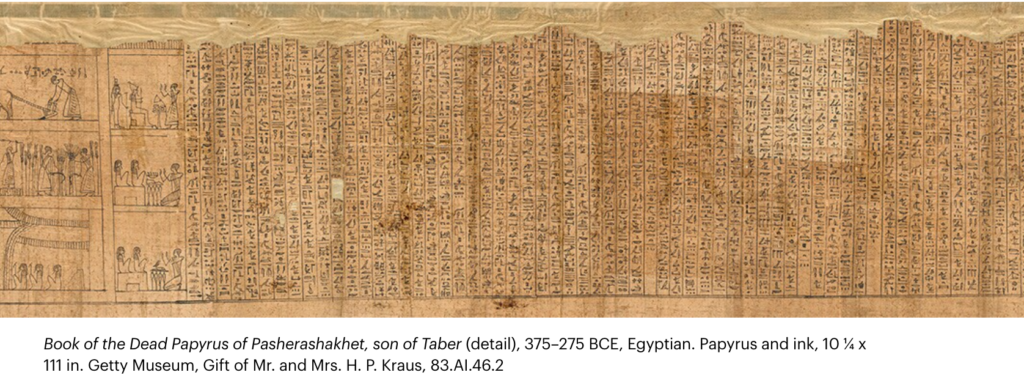

“Book of the Dead” is a modern term to describe a series of ancient Egyptian ritual spells (instructions and incantations).

These helped the deceased find their way to the afterlife and become united with the sun god Re and the netherworld god Osiris in a continual cycle of renewal and rebirth.

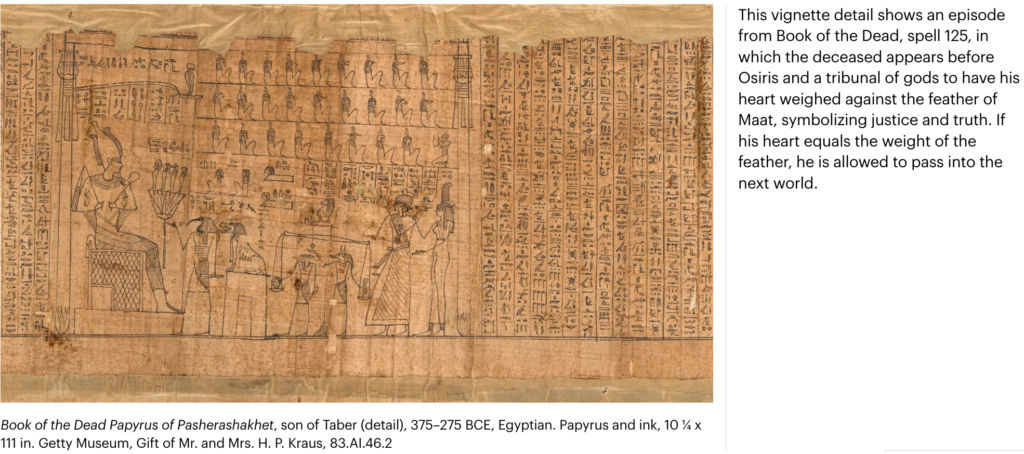

There are nearly 200 known spells, but they weren’t collected into books in our current sense of the word. Rather, assemblages of spells were inscribed on objects from mummy wrappings to coffins to figurines to papyrus scrolls, all meant to accompany the dead in the tomb. They provided instructions for the various challenges the deceased would face on their journey. Spell 125, for example, lists a number of misdeeds they must deny having committed in life when they appear before Osiris.

Getty’s Book of the Dead manuscripts include seven papyri and 12 fragments of linen mummy wrappings that are now undergoing new scholarship spearheaded by Foy Scalf, an Egyptologist who is the head of research archives at the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures at the University of Chicago. Along with Getty’s ongoing provenance research (discussed below), Scalf is studying the texts and preparing translations and analysis in order to place them within the broader context of the long history of the Book of the Dead.

The group of writings that we call the Book of the Dead developed from multiple different sources, including earlier funerary inscriptions, priestly oaths, and household spells. It was likely embedded in a strong oral tradition, as most people could not read or write. By the New Kingdom, starting around 1550 BCE, scribes started writing Book of the Dead spells on papyrus scrolls. Vignettes often illustrated key points in the text, as in the example above from spell 125, in which the deceased has his heart weighed in the presence of Osiris. Book of the Dead spells were meant to be spoken aloud. Priests would read from scrolls during the funeral, and much of the text is written as direct speech that the deceased is envisioned reciting in the netherworld.

Exploring Getty’s Book of the Dead

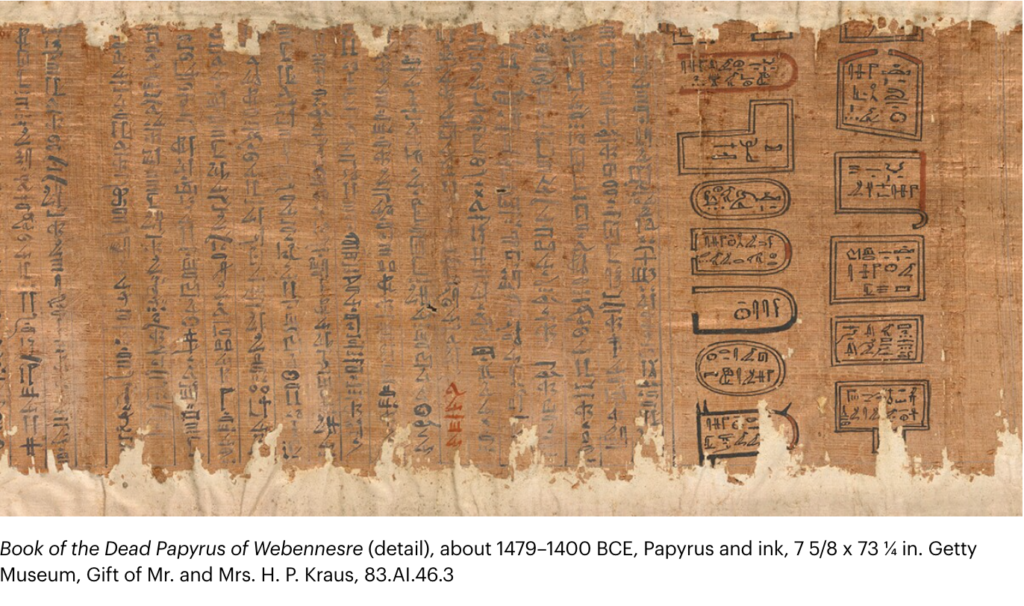

Getty’s collection spans a wide timeframe, which provides an exciting opportunity to examine how the Book of the Dead evolved for more than 1,000 years, and how it was used by the Egyptians.

The earliest text we own is an 18th Dynasty papyrus that was made sometime around 1450 BCE, during the height of Egypt’s New Kingdom The papyrus, which belonged to a woman named Webennesre, includes spell 149, in which the deceased encounters fourteen “mounds” in the afterlife, each of which has its own inhabitants. These mounds are illustrated at the far right of the scroll.

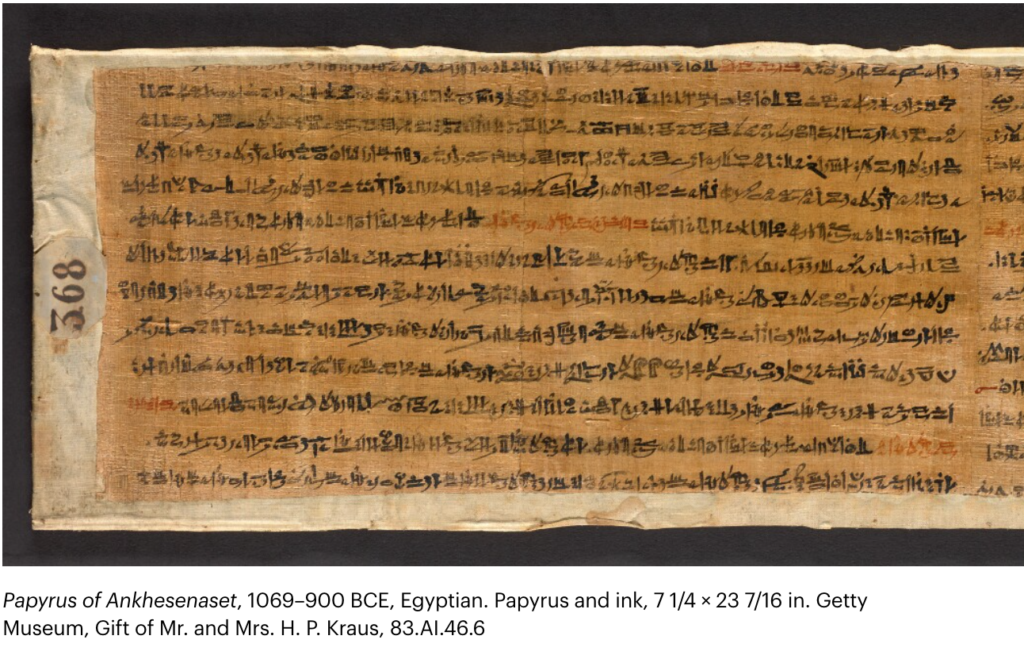

Three papyri date from a later phase called the Third Intermediate Period, around 1069-664 BCE, a time of political fragmentation and instability. Despite changes in the socio-political landscape in Egypt, traditional funerary practices, including the Book of the Dead, endured. In the area of Thebes, shorter papyri without vignettes became fashionable. Our three papyri belonged to women named Nesmut, Aset, and Ankhesenaset, all of whom were priestesses and ritual “singers of Amun” at the god’s temple in the Karnak complex of Thebes. We are hopeful that by examining our collection, we can better understand why particular collections of spells were popular in different time periods and regions.

From Egypt’s Late Period comes a recently acquired faience ushabti dating to about 570-526 BCE. These mummiform figurines were animated in the afterlife by reciting the spell (spell 6) inscribed on their bodies. Once alive, they could perform labor on behalf of the deceased. This ushabti is one of 336 that were excavated from the tomb of a man named Neferibresaneith at Saqqara, Egypt.

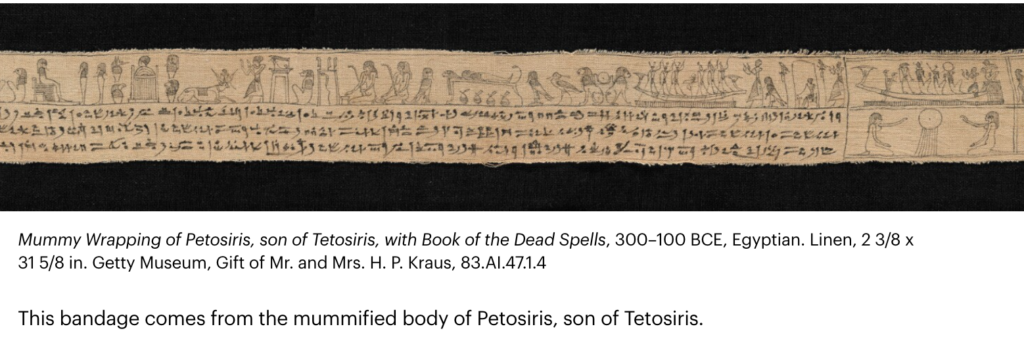

Over time, we can see how people’s relationship with the Book of the Dead became even more personal. One way in which this evolving relationship manifested was in the use of Book of the Dead spells on strips of linen that were wrapped around the mummified body, putting the spells in direct physical contact with the deceased. This practice was popular from about 400-100 BCE.

Our mummy bandages all belong to the Ptolemaic Period, around 305-30 BCE, when Egypt was under the rule of the Greek successor dynasty that followed Alexander the Great’s conquest. Book of the Dead papyri continued to be produced during this time as well, and three of our papyri are Ptolemaic in date.

The bandages come from the burials of three individuals: Petosiris, son of Tetosiris (six bandages); Petosiris, son of Nanesbastet (four bandages); and Nanefbastet, son of Taneferher (two bandages).

Uncovering the Collection’s Ownership History

It’s important to trace the ownership history of the manuscripts—how they were collected and sold and what those relationships mean. This information can help contextualize related manuscripts, reveal connections to older sale groups, or document patterns of site discovery over time. In short, to know an object, you have to know its history, and that in turn allows you to tell richer stories.

In the 19th century, English scholar and collector Sir Thomas Phillipps of Thirlestane House purchased the papyri and mummy bandages as part of his personal quest to create one of the largest manuscript collections in the world. After Phillipps’s death, they remained in his family until the mid-20th century; eventually, they ended up with bookseller Hans P. Kraus, Sr., in New York, who together with his wife, Hanni, donated them to the Getty in 1983.

But the history of the objects requires some more sleuthing. For example, additional bandages from the same three mummies represented in our collection are now found in collections around the world. Researching how they were split up is one major piece of the puzzle. Another goal is to identify the present locations of the full group of ushabtis discovered in Neferibresaneith’s tomb; so far we’ve found them in places from San Jose, California, to Cuba, from Poland to India.

Understanding how Phillipps acquired his collection is part of Getty’s ongoing research and will help us reconstruct the movement of Egyptian antiquities in the 19th and 20th centuries.

We’ve begun to piece it together, discovering that a New Kingdom papyrus that also belongs to the Phillipps group (but does not contain Book of the Dead spells) was sold at auction in 1831, and that Charles Augustus Murray, who was the British consul-general in Egypt from 1846 to 1853, supplied Phillipps with other mummy bandages.

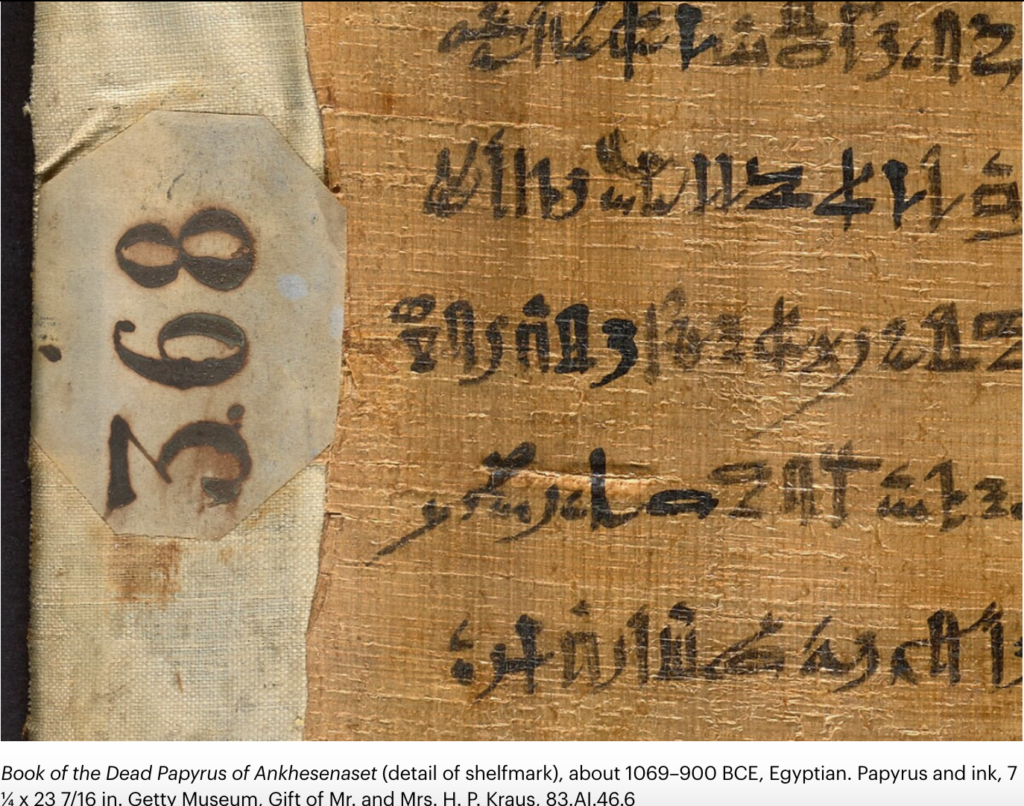

Finally, there are intriguing clues on some of our papyri in the form of unusual, handwritten shelfmarks on octagonal labels. Phillipps didn’t use this kind of label, so they must have been added by a previous owner.

Getty’s Book of the Dead collection undoubtedly still holds many secrets to be revealed about both its ancient and modern histories. We hope to have an online catalog ready in 2024. In the meantime, you can learn more at Google Arts & Culture and our online collection pages.