–By Narrative Thread

Despite receiving praise for its story and lore, particularly in contrast to the previous entry in the series, Diablo 4’s narrative design — and, by extension, its campaign — is the blandest ingredient in this demon-slaying cocktail

It starts with a cutscene — a wanderer, assaulted by weather and wildlife alike, barely clinging to life, marching along snowy peaks as a narrator gives us just the right amount of exposition to set the stage. It’s a short scene, and it does a fairly good job at establishing the tone of the game (it’s dark! It’s grim! it’s not cartoony, ok?!) It also manages to reveal one of the big, glaring flaws of its narrative design, right from the get-go: who is this wanderer? why are they wandering? Where are they wandering from, where are they going to? Who’s to say — definitely not this game.

The Blank Slate

It’s not a new recourse, of course. Games have been using different versions of this trope for as long as there have been games with stories; after all, it’s not like Super Mario Bros. gave us much to go on in terms of Mario’s personality or his history. You’re a plumber: here are some pipes, some enemies, and some wildly suspicious mushrooms — go do your thing. Countless games have had protagonists with little to no personality and/or voice, a trick that ostensibly allows players to project themselves onto the characters, and definitely saves some bucks in script writing and VO recording. There’s nothing wrong with the trope per se, but it’s also not an all-purpose tool to be used in every single game — it’s important to recognize when it makes sense to have it.

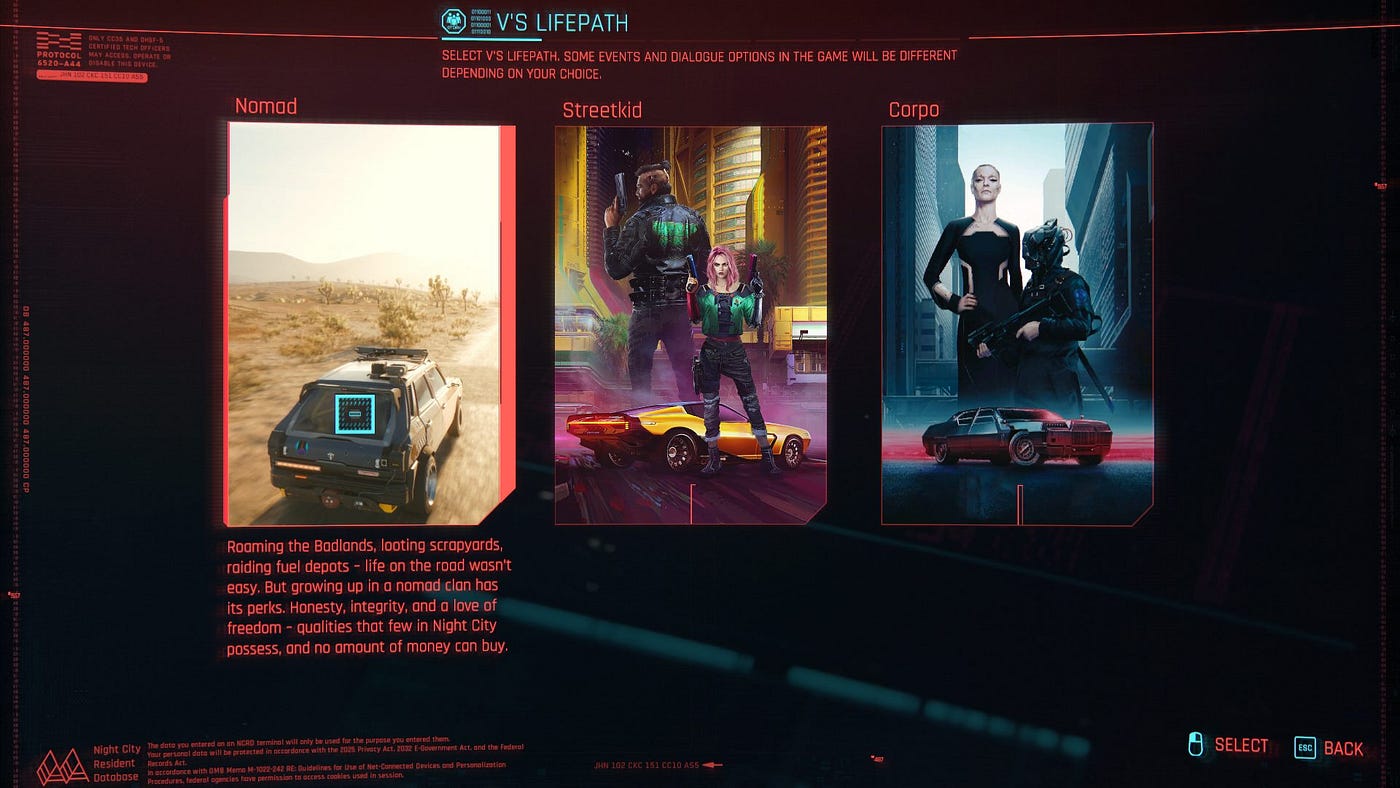

In fact, the trend in story-driven RPGs is to give players the tools to customize their character’s origin: from Cyberpunk 2077’s lifepaths to Baldur’s Gate 3 and Divinity: Original Sin 2 origin characters — knowing where a person comes from is a crucial part of figuring out where are they going. In CP2077, my V wants to “make it to the big leagues” because she comes from a poverty-stricken ghetto and has failed at her attempt to start anew in a different city. It’s the crux of the game’s narrative, the first piece of the domino that sets everything in motion.

Diablo 4, by contrast, offers nothing. Not even the barely-there origins of Diablo 3’s classes, which all pretty much amounted to “You’ve been sent by your order/guild/tribe to investigate the fallen star” — it’s not much, but it’s something. The Wanderer in D4 is a real blank slate, and in a game intent on telling its story through character-driven cutscenes, it sticks like a sore thumb. When Lorath — the grumpy, wizened scholar that narrates the end-of-act scenes — praises the wanderer’s feats of strength against the demons of hell it rings hollow, because we don’t know why are they so much stronger than everyone else, or where do their powers come from. It means equally nothing when he talks about the wanderer’s moral fortitude in withstanding Lilith’s corruption — we have nothing to tie it to: no incorruptible mentor, no loving mother, no home to go back to, nothing. Every time the game tries to make us connect emotionally to any of its characters, it fails miserably, because the connection cannot be established through such an empty vessel of a character. The wanderer is an all-powerful superhero devoid of past, personality, and agency, willing to throw themselves against primordial evils with little to no motivation and zero personal stakes. It’s just not possible to build a compelling story from them.

The Exposition Ghosts

That’s one fatal flaw in Diablo 4’s campaign, but still there’s another crucial way in which Blizzard’s narrative design unambiguously fails — the use of exposition ghosts. Not a new thing by any means, having ghosts or holograms or any such thing explain the story to the player without giving them a chance to intervene is a techinque the studio has been using for decades, in World of Warcraft and in Diablo 3, for example. It’s also lame, and lazy as hell.

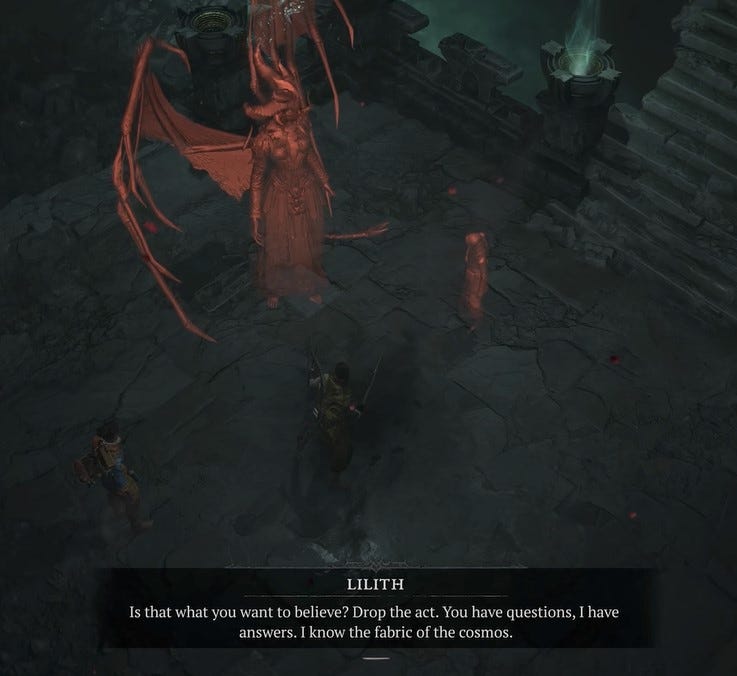

Diablo 4 wants to tell you what its main antagonists are doing, but it doesn’t want you to catch up with them until the game progression demands it, so it invents a flimsy excuse to give you this information in semi-translucent flashbacks. You’ve drank the blood of Lilith so you see visions of the things she does. Not everything she does, mind you — expect no visions of Lilith eating a steak, polishing her horns, or taking a shit — you see visions of the plot-relevant things she does. It’s hacky and immersion-breaking, and above all, it’s extremely overused. At a certain point as you play the game, you become used to exploring incredibly gory and evocative dungeons only to be rewarded at the end by an exposition dump in the shape of talking ghosts — the princess is in another castle, you just missed her! Here’s Lilith looking menacingly at the camera and telling you exactly where to go next. Here’s Inarius doing something extremely important to the story and the lore — ten minutes ago.

I can only imagine how much stronger the story would be if the game allowed you to connect the pieces yourself, if the dungeons showed only ominous signs of hidden, unspeakable evil, only glimpses of Lilith’s plan. As it is now, she quickly becomes a cartoon villain, delivering evil monologues with a complete lack of self-awareness, and the story amounts to little more than a wild-goose chase through different biomes, peppered with boss fights and exposition dumps.

The Weakest Link

There’s plenty to nitpick apart from these two main issues. For one, having the actual creators of humanity, Lilith and Inarius, be directly involved in the story from the beginning doesn’t really work for me, as it cheapens their status as mythical figures from which entire religions spawned. (Spoiler Alert: What’s the point of having lore with multiple faiths, each with its own cosmogony, when it turns out the creator of the world is just chilling in a church in the mountains, casually interacting with the clergy). I’m also not a fan of having the player essentially just follow along and fight minor demons throughout most of the game. There are no twists, and no changes to the script. You’re following Lilith, you fight any and all demons on the way, fin.

The conclusion, sadly, is that the campaign is a total bust. It’s never engaging, and it’s also never presented as the real meat of the game. We’re told from the beginning that the campaign is something to be experienced once and subsequently skipped in all the following characters we create — and we’re going to have to create a bunch of them, at least as many as seasons we want to participate in. It’s almost a nuisance, the homework we need to finish before we can jump to the endgame — the endless loot treadmill, the clickety-click grind at the end of the story. All those looking for an immersive tale set against the backdrop of a decaying gothic world need not apply.